Today I’m delighted to welcome John Mayer to Virtual Book Club, the interview series in which authors have the opportunity to pitch their novels to your book club.

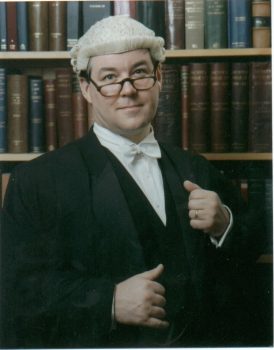

John Mayer left school aged fourteen because the school was in a gang war zone and he wasn’t learning enough to satisfy his intellectual curiosity. He read privately for a year in the Mitchell Library in Glasgow before becoming the youngest member of the Institute of Mechanical Engineers in Scotland. Through the 1970s he was an Indie Record Producer flying his own plane and making records which are still played as anthems today. In 1992 he became an Advocate in the Supreme Court of Scotland where he specialised in international child abduction: rescuing the children, not abducting them, of course.

In his youth, John was shot! Twice! Once in Glasgow, Scotland, and once in New York City. Don’t ask him what happened to the other guys. John has always tried to bring an intellectual passion to everything he does. But he also believes that his best writing comes when he’s feeling just what his characters are feeling. Those two characteristics shine through his works in The Parliament House Books.

Q: Andy McNabb’s own story reads like fiction. Found in a carrier bag abandoned on the steps of St Guy’s Hospital, attended nine different schools over seven years, became a petty criminal, visited by an army recruitment officer in juvenile detection and offered early release if he joined up. I worry that my author biography is deathly dull. Have you ever been tempted to jazz yours up?

A: I don’t need to jazz up my life story. My story is every bit as colourful as McNabb’s. I was born in a Glasgow gang war zone and by aged only four I’d seen my first murder being committed. By aged fourteen, I’d seen a few more and had been shot. In that regard I’ve err, done a few things I can’t talk about.

I walked out of school aged fourteen because the poor teachers could only do crowd control and were teaching us nothing. I went straight home and told my mother why I’d walked out. She hugged and kissed me before suggesting that I ride my bike nine miles to and nine miles from Glasgow’s biggest library (The Mitchell) every day. That way I was free to learn what I thought was important – and I did. I became the youngest Member of the Institute of Mechanical Engineers in Scotland aged eighteen. I stayed in engineering until I had the urge to become a record producer. I walked out of engineering while the HR Director was pulling me back shouting ‘John, you’re our brightest. Who’s poached you? Please come back.’

During my record producing days I was flying my own aeroplane and sealing deals by clinking champagne glasses aboard the Warner Bros yacht down in Cannes. In New York very late one night, I jumped in to save a girl from being raped in a subway station. Her attacker shot me but after a bit of treatment the girl and I were OK.

I always knew the real intellectual challenge of my life would be as a lawyer. I’d done deals with lawyers and many of them thought I already was one. I remember the day I gave up producing records and started an eight year journey towards being an Advocate (Barrister).

In Parliament House, my speciality was in the Hague Convention Against International Child Abduction. I’m proud to say I’ve had many dozens of abducted children found around the world and returned to their rightful parents. The African child in the Parliament House Books called Ababuo is based on a real child whom I had returned to Africa. Richard Branson took her on his inaugural flight to Johannesburg. And yes, she even got to wear his captain’s hat.

Now, as a novelist, I’m free to tell the stories that have rattled around Parliament House for nearly 500 years.

Q: Who gave you your first encouragement as a writer?

A: That’s an easy one. At aged eleven, after taking the 11+ Exam in Scotland, my mother and I went to see my school teacher, Miss Ralph. In Scotland, in my day all women teachers were Miss. In answer to my mother’s question ‘What do you think he should be?’ Miss Ralph’s eyes misted over: ‘Oh Mrs Mayer, the boy is a born storyteller. A lawyer or a writer. He should be both, if he can.’ My mother and I walked home on air that day.

Q: When did you first feel you were becoming successful as an author?

A : Before I began writing fiction I had written text books and articles and also been published in hardback when I wrote a non-fiction book called Nuclear Peace. I was on a ten-week tour of the USA promoting that book when I was asked to do a radio gig in New York. My publicist told me I had to rehearse a precisely 28 minute segment: I would be asked no questions but should say something about myself, explain the point of the book and then read passages from the book.

I remember going to this vast barn of a place in Brooklyn where a desk, chair and microphone were set up at one end. My papers just said the station was called ASR; which was one I hadn’t heard of. I was well rehearsed, all set up and the levels were nearly ready when I asked what ASR stood for. It was American Schools Radio and I was about to broadcast to 40,000,000 (yes 40 million) schoolchildren and their teachers.

I was inundated with questions by email and later did so many video chats I lost count of them. That felt like my first success as an author.

Q: Arnold Baffin said that every book is the wreck of a perfect idea. Discuss.

John Mayer : Arnold Baffin is wrong. To say that ‘every’ book is something must be wrong because not all books contain or achieve the same things. Many are downright vacuous and only a few are capable of ‘wrecking’ anything. Besides, nothing is perfect to begin with. Mr Baffin wouldn’t have lasted five minutes in Aristotle’s logic classes. He might have fared a little better in Socrates’ discursive classes, but I doubt it.

Q: What is it about your series of novels that you feel makes them particularly suitable for book clubs?

A: I spent twenty years as a trial lawyer, persuading juries that my case was to be preferred: and more often than not, I did persuade them. During that time, I also wrote legal pleadings which are a way of trying to persuade a judge that you have presented – in writing – all of the facts of the case and that your interpretation is to be preferred. I write for book clubs so that readers can BE the jury. Each member (of the club) can take part in discussion and argue amongst themselves about the facts and circumstances of the story and arrive at their final verdict.

Q: Twenty words on why your book should be a reader’s next read…

A: Any crying child howling about injustice can tell you how deeply it hurts. Or, read The Parliament House Books.

Q: If you were trying to describe your writing to someone who hasn’t read anything by you before, what would you say?

A: I try to write intelligently, hoping to convert feelings into words. I think I can convey the atmosphere in the spaces – grand and small, lavish and filthy – which my characters occupy because for twenty years I practised law at the highest level in Parliament House and I’ve been in – and out – of every jail in Scotland. I know very well the awful consequences when legal judgements are twisted or outright usurped.

Q: Where is your series of books set and how did you decide on the setting?

A: The Trial is set in both of Brogan McLane’s worlds. Parliament House in Edinburgh and the Calton Bar in Glasgow. He practises law at the Bar of the Scottish Supreme Court, but often finds that his friends in the Calton Bar have more integrity than his opponents in Parliament House. All of the books in the series centre around those places.

I carried the slogan for this series of books around in my head for many years before writing the first line. That slogan is of course ‘Low Life in High Places in the Old Town’.

Q: Did you have a title for the first novel in your series or did one suggest itself as you wrote the story?

A: The first book in the series is an homage to Franz Kafka’s genius work of the same title; The Trial. My concern was whether I could write a first book in the series which was worthy of comparison with his writing. I re-read Kafka’s The Trial three times before deciding that I could try. I wanted to be unashamed that I was trying this mighty challenge. It’s the only way I know how to do anything: Full On.

As for the other books in the series, I start with one word, which is the subject matter of the book and expand from there. For instance, The Cross, The Cycle, The Boots, The Order, The Bones.

I must say though, that I did get lots of professional help before publishing The Trial, which is now in its second edition. I was exhilarated when readers started to say things in reviews like ‘Better than Grisham’ and ‘Mayer is a master storyteller’ and ‘Gripped me to the last page.’

When High Court Judge, Lord Aldounhill, is found dead after a transvestite party in his sumptuous home, those who know the killer close ranks and need a scapegoat – who better than ‘outsider’ Brogan McLane?

“An excellent read that takes you through a labyrinth of legal and criminal underworld secrets: a real insight into the layered workings and politics of the criminal justice system. “

Click here to look inside or buy

Q: What is the central conflict in your first novel?

A: Whether justice will ensue or will be subtly nudged in a catastrophic direction.

No country or empire has ever produced a perfect legal system. The reason for that failure is best understood by knowing about David Hume’s famous philosophical bridge: the one which cannot be built because it tries to connect the way the world is with the way it ought to be. That conflict has been present since the dawn of Greek civilisation. That conflict is what I try to weave into my stories.

Q: Is your writing inspired by any real life events? And, if so, how do you deal with the responsibility that comes with that?

A: When my clients would ask me what would happen in court, I was fond of telling them the analogy of the patient and the doctor. You have a medical problem, so you see your GP. She refers you to a specialist. He sets up your clinical operation. He and his team perform the operation with skill and all is well. You leave hospital cured.

In the legal case, your lawyer instructs the specialist (me) and we go to court. We have a kind of clinical hearing with rules. So far, the analogy holds. But, then I have to tell them that while I am trying to cure their problem, there is a barrister on the other side trying to stab them to death.

Things get to life and death very quickly in court. That responsibility would always weigh very heavily on me. If I got things wrong, companies collapsed and people lost their jobs, the government got to do something that thousands of people objected to, children never saw their parents again or the wrong person was led away to spend twenty years behind bars.

I dealt with that in two ways. Firstly, after a week in court, on Friday nights my wife would make me a good dinner then I’d get blind drunk on Lagavulin 16-year-old whisky. On Sunday morning, I’d start preparing for my case in court on Tuesday.

Q: Do you incorporate any real life characters into your novels? If so how?

A: I do in fact incorporate real characters, but I blend them together to form fictional ones. Tucker Queen the rat-catcher is a real person. The abducted African girl in the second novel, The Order, is also real; though I didn’t get to know her very well. She lives in my imagination quite a lot. I can only hope her life worked out well after I’d won the court order to return her to Africa.

I also thinly disguise certain good guys; such as some judges whom I admire very much. In my fourth novel in The Parliament House Books titled The Trust, I’ve used a real character who is a girl of eight years old. However, in the book (not yet published) she’s twenty-four, an Advocate in Parliament House and becomes Deputy National Security Commissioner. Her parents say I’ve captured her to a T and we await her development with keen interest.

Q: I am a keen walker. Geoff Nicholson, author of The Lost Art of Walking wrote, “There is something about the pace of walking and the pace of thinking that goes together. Walking requires a certain amount of attention but it leaves great parts of the time open to thinking. I do believe once you get the blood flowing through the brain it does start working more creatively. Your senses are sharpened. As a writer, I also use it as a form of problem solving. I’m far more likely to find a solution by going for a walk than sitting at my desk and ‘thinking’.” If you agree, please comment on how walking helps you. If you disagree, how do you unknot your thinking?

A: I’m not a walker but I am a solo sailor and I find the same sort of thing when I’m on the sea. I have to check around the sea for approaching vessels (or sharks) and cast my eyes on important things like instruments aboard the boat. But often there will be a space when there’s nothing to do but slip along on a fair wind: that’s when something that might have been troubling me about a passage I’m writing comes up. I trust my feelings – or more accurately my ‘sensibilities’ – and I know when I have a good idea or a good solution presents itself from my unconscious to my conscious mind. That’s very satisfying.

Q: In her essay about Half of a Yellow Sun, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie says that Girls at War and Other Stories is about what happens when the shiny things we once believed in begin to rust before our eyes. What form do those shiny things take in your novel?

A: I like that quote because it resonates with the ethos of The Parliament House Books. There are no votes in justice and injustice. Only when these touch people’s lives directly do they feel the pain of what a legal system can do to them and perhaps their loved ones. I’ve never met a happy ‘winner’ of a legal case, only a relieved one. We trust the shiny things: the courts, the judges, the lawyers, the process all to work towards justice, but nothing could be further from the truth. I’ve been told by a judge that my client, who’d travelled from Australia to give evidence as to her child’s abduction, was to be asked no more than twelve questions. When shocked, I asked if that included her name and address, the judge said he’d report me for insolence. Even though we had a rock solid case of abduction, that woman never saw her child again. Parliament House is over 500 years old and such injustices have happened in it since the day it opened. My first novel – The Trial – has plenty of such injustices built in. But now there’s Mr Brogan McLane QC to put things right.

Want to find out more about John and his writing?

Website : http://www.parliamenthousebooks.com/

Twitter : https://twitter.com/johnmayerauthor

John is generously giving away a Parliament House Series ebook to the first five readers to follow him on Twitter after reading this interview. Just send your email address via DM on Twitter to @Johnmayerauthor.

Facebook : https://www.facebook.com/theparliamenthousebooks

Get your hands on all three prequels as part of a box set for only £1.99.

Remember, if you enjoyed this post please share it. If there’s anything else you’d like to ask John please leave a comment.

To have future posts delivered directly to your in-box, visit the sidebar on the right and subscribe to my blog, or to find out about new releases, competitions and freebies, subscribe to my newsletter and grab your free copy of my novel, I Stopped Time.