Looking for an overview of my writing journey? Keep reading for more background on my life, what led me to become an author, my passion for writing and reading, and advice for aspiring writers.

Introduce us to your younger self

I was brought up in Merton Park, close to Wimbledon. Despite this, I’ve never been to the tennis, but I did see the Wombles once. They were surprisingly tall and had deep voices.

My family has a history of artistic tendencies. My father’s father was a cabinet-maker and a talented amateur artist. The other – my mother’s father – was a composer, whose children all found work in the music profession. My uncles, both flautists, played on the Beatles, Fool on the Hill, while my mother’s various claims to fame include being an expert on Tudor music and performing on the infamous Finger of Fudge advert. As children, we were encouraged to attend music lessons, pushed onto the stage and into compulsive exam-taking. These experiences left me with a dislike of classical music, terrible stage fright and instant panic on entering exam rooms.

During my formative years, I won a Blue Peter badge for naming Goldie the Labrador; had two pieces of work displayed in the Vision On gallery; won a silver shield at the Kingston Music Festival for playing The Entertainer on the descant recorder. I also once played James Galway’s golden flute. None of this mattered because, to my shame, I failed the interview to appear on Crackerjack for not knowing the names of all of the Beatles.

I understand you were one of five children

I was! Being part of a large family has both advantages and disadvantages. Never having your parents’ undivided attention fell into both categories. Rarely finding a place in which it was possible to be quiet was difficult for me. I found solace in reading, which remains one of the only legitimate excuses to be unsociable.

Do you have any writing qualifications?

Apart from my Catholic upbringing – which Hilary Mantel claims is essential for all writers – I’m quite unqualified. If this disappoints you, then I apologise. However, if you have that gnawing feeling that there’s a book inside you trying to get out, I’m here to tell you that, unfettered access to a computer aside, the only other thing you need is time. Quite a lot of it.

How and when did you start writing?

I watched a programme in which Rick Stein described how he came to become a chef as a food enthusiast. I began my writing journey as an enthusiastic reader and a lover of words. From the days when I was glued to Jackanory as a child, to my love of Tom Wait’s song-writing, I’ve always admired storytellers.

My writing journey really kicked off when I embarked on my first novel at the age of thirty-five. Too personal to ever see the light of day, it took four years to complete.

How did you carve out time to write when you had a full-time job?

You make time. I do my best writing when I’m busiest. I become very disciplined – and far more selfish with my time. Often, when writing Half-truths and White Lies, I came home from work worn out and sat down at my computer without a clue what I was going to type. That changed once I’d got the characters right. After that, they seemed to write themselves.

What were the greatest challenges you faced on your writing journey?

The greatest leap of faith in my writing journey was the decision to let other people read what I’d written. You reveal so much about yourself through your writing. Even if you don’t use personal experiences, assumptions are made. If your novel is based partly in truth, people assume every detail is true.

It’s very difficult to be subjective about whether what you’ve written is any good. I was fortunate in having a group of friends who were prepared to be critical and wouldn’t have dreamt of flattering me, and they all come with me on my writing journey. Based on their feedback and, armed with a copy of the Writers’ and Artists‘ Yearbook, I began to submit my work to literary agents.

How did they respond?

Rejections, when they came, carried the same message: we are not taking on any new clients at the moment. But two replies arrived with handwritten notes. They both said, ’You can write, but your work is completely unmarketable’. One recommended using The Literary Consultancy for a professional review. I was intrigued enough to invest.

Six weeks later I received a twelve-page response. TLC suggested that I should turn my quirky coming-of-age story into a crime novel. Horrified, I put the manuscript away for six months but I couldn’t forget about it. I came around to the idea, asking myself why shouldn’t I play around with it? Once I finished my new draft, I resubmitted it. Two agents replied immediately, asking for the full manuscript. I signed with one of them.

What was your reaction when you found out you’d won the Daily Mail First Novel award?

Half-truths and White Lies, winner of the Daily Mail First Novel Award, with cover quote by Joanne Harris

To be honest, I was completely gob-smacked. I had only found out about the competition – two days before the closing date for entries – when attending the Winchester Writers’ Conference. My real incentive for entering wasn’t the thought of winning; it was to discover if I was a contender.

The timing of the announcement was perfect. I had left my job of twenty-three years in September. Three weeks later the honeymoon period was well and truly over. Every time I turned on the television there was talk of doom and gloom. I began to worry that leaving a secure job at the onset of a recession hadn’t been the best of ideas.

The call from Transworld came when I was at home on my own and, because I was alone, I wasn’t sure how to react. With no one to ask, ‘Wait, did that just happen?’ I had to put down the phone, pinch myself and call them back.

The weeks that followed were heady. It was a thrill to see my name in print in the Daily Mail and The Bookseller. Joanne Harris, who I greatly admire, provided the cover quote. I was going to be the Next Big Thing.

Except that I wasn’t.

In a year when book sales took a nose-dive, Half-truths and White Lies sold reasonably well. Told that my publicity would be taken care of, I did what I had always done. I wrote.

My big reality check came in late 2009. Transworld turned down my next novel (what has since become A Funeral for an Owl.) It was beautifully written, they said, but it wasn’t women’s fiction. I hadn’t realised the implications of being published under their Black Swan label. I’d been pigeon-holed – and my work didn’t fit.

What then?

My writing journey didn’t just stop. Over the next four years, I produced two further books, books that I’m proud of. Had I been under contract, I would have been up against deadlines, but I wasn’t. Instead, I had the luxury of time to add layers to the plot, depth to my characters and a sense of time and place. I Stopped Time was a tribute to my grandmother who lived to the age of ninety-nine. It’s also an homage to the pioneers of photography. These Fragile Things was an important book for my writing journey. Though I’m not religious, it’s my reaction to aggressive atheism, which I feel is another way of stifling personal freedom.

But you continued to pursue a traditional publishing deal?

At the time, self-publishing was in its infancy. I paid good money to be told that no serious author should consider it. By 2012, I was touting three novels around the market. Believe me, this isn’t a position you want to be in. On the bright side, rejection letters were more flattering. Now they read, ‘It’s not for us, but with your credentials we feel sure that you’ll be snapped up.’ I began to feel like the lady character in Michael Chabon’s Wonder Boys who goes to the same writing conference year after year with a slightly different version of her novel, and each year it is rejected for a slightly different reason.

That same year, I attended two conferences. The first was given by Writers’ Workshop who offered the opportunity to submit my opening chapter for critique by a professional which would be discussed on the day. There was also the opportunity to pitch your work ‘live’ to a panel of agents in front of an audience.

On the face of it, the critique seemed to be the less harsh of the two options, but people came out of the room ashen-faced and with their manuscripts covered in red ink. I offered a shoulder to cry on while waiting my turn. When at last I took my place at the table there were no red marks on my manuscript. I had submitted the opening chapter of These Fragile Things, my least commercial novel to date. “You didn’t like it,” I said. “No,” I was told by the editor. “I loved it.” I burst into tears on the poor woman, but for all the right reasons. Her advice was not to change a single word, but that my enquiry letter needed work.

Buoyed up, I was ready to pitch my novel to the panel of agents. The only problem was, they didn’t want to hear my fantastic opening chapter. They wanted to hear my enquiry letter. The letter I’d just been told sucked. Despite this, the agents commended my passion and commitment, and I came away with five panel members offering to read every word I’d written. They all rejected me.

What changed your mind about self-publishing?

I went to the Writers’ and Artists Self-Publishing in a Digital Age Conference – probably the most crucial moment in my writing journey. Here were authors who’d enjoyed commercial success, but had been dropped by their publishers after their latest releases didn’t sell quite so well. They were rubbing shoulders with first-time authors who had put their debut novels out there for 99p and sold 100,000 copies in the space of a year. There were also writers who, after years of trying the traditional route, had taken the plunge. It was a publishing revolution. All I had to decide was whether I was in or out?

I decided I was in. On Christmas Day 2012 (within a month), I published I Stopped Time and These Fragile Things.

We hear a lot about the importance having an author platform. What does that mean?

Start as early as you can. Setting up a basic website is cheap and easy. Utilise Facebook and Twitter to full advantage. Be active on Goodreads and other reading forums. Perhaps you’re a visual person, and you’ll be inspired by images you find on Pinterest. Find what works for you. Social media has enabled me to access reader and author communities I couldn’t possibly have accessed in person.

When I was traditionally published, even with the services of an agent, I felt very much alone in an industry I didn’t understand. But when I attended the London Book Fair as an author, I found I knew dozens of authors – people I’d interviewed or reached out to on the internet, or who had reached out to me. Networking gave me a leg up on my writing journey.

What advice would you give to anyone who is thinking about becoming a writer?

Get started. A novel starts with one small idea. You don’t have to work out how the book is going to end before you begin. If the characters are right the rest will follow.

Be disciplined. When I worked full-time, I aimed to write one chapter a week. In a year’s time, I had a first draft. (It helped that we didn’t have the Internet at home in those days!)

The filmmaker, Peter Jackson, places a great deal of importance on tiny details in costume design and builds intricate pieces of sets that will only appear fleetingly on the screen. I’ve taken the same approach on my writing journey.

Read as much as you can. Be critical, but don’t let it destroy your love of reading. Keep an eye on what’s selling. Unless you’ve written something brilliant and original enough to start a new trend, your work will need to sit neatly with what’s out there.

Learn as much as you can about the publishing industry. Budget to go to a couple of conferences a year. Things are changing very rapidly and, unless you stay on top of developments, you’ll be left behind.

Alison Bavistock describes writing as lonely, isolating and fattening. My writing journey has also been liberating and therapeutic. I assure you: it will be worth it.

What do you think makes a great novel?

A great novel has to transport you somewhere. There have to be a few deeply flawed but sympathetically written characters. The speech and descriptions need to sound authentic. There must be a love interest, even if the love is unrequited. And there needs to be a tragedy.

Whose writing do you admire?

Apart from John Irving and Thomas Hardy, I love Louis de Berniers, Jennifer Egan, Maggie O’Farrell, Ali Smith, Sarah Hall, and E. Annie Proulx.

What are your favourite novels?

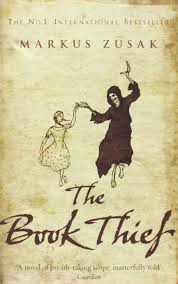

The Book Thief by Marcus Zuzak is the book that I recommend to people who tell me that they don’t enjoy fiction, because it’s steeped in fact. The author tackles extremely sensitive subject-matter with originality and simplicity, which is perfection. I got to the very end before I learned that Marcus Zuzak has authored several award-winning children’s books. It explained much about his writing style and his deep understanding of his main characters.

The Book Thief by Marcus Zuzak is the book that I recommend to people who tell me that they don’t enjoy fiction, because it’s steeped in fact. The author tackles extremely sensitive subject-matter with originality and simplicity, which is perfection. I got to the very end before I learned that Marcus Zuzak has authored several award-winning children’s books. It explained much about his writing style and his deep understanding of his main characters.

I find myself coming back time and time again to Tess of the D’Urbervilles by Thomas Hardy. It remains relevant and contains the most perfectly flawed heroine; innocent, naïve, wronged. And, ultimately, deadly. I feel that I catch glimpses of the England that Hardy describes when I’m out walking in the mountains.

The Prince of Tides by Pat Conroy is a difficult, rich and rewarding read. Don’t be put off by the film which detoured neatly round the more shocking elements of the storyline, leaving very two-dimensional characters.

My favourite author is John Irving. His use of cause and effect has had a great influence on my writing journey. As for which of his novels to shortlist, I’m torn between Cider House Rules and A Prayer for Owen Meany. Both are life-changing. I particularly love John Irving’s use of themes and challenging viewpoints. I’ve never been to New England, but have come to know the area through his writing.

E. Annie Proulx wrote the most extraordinary main character in Quoyle in The Shipping News but her use of language is so full of warmth and humour and sadness that you can’t help but love him.

What can we find you doing when you are not writing?

I have a keen love of the British countryside. This stems largely from a ten-year stint with the Boy Scouts, firstly as a cub leader and then, since knowing I shouldn’t swear resulted in compulsive outbursts, with the less shockable Ventures (who taught me a few new ones to add to my repertoire). I take regular walking, climbing and photography trips, and think of Ambleside in the Lake District as my second home.