Meet the author: Kathleen Jones

On a journey from fact to fiction

Today, I’m delighted to welcome biographer, poet and novelist, Kathleen Jones to my blog. Kathleen is one of seven entrepreneurial authors who has contributed a novel to the limited edition box-set Outside the Box: Women Writing Women which showcases the most exciting fiction being released by authors who are in full charge of their own creative decisions. But more on that later.

Kathleen was brought up on a remote hill farm in the English Lake District. Though she can’t remember a time when she didn’t write, she started writing for publication as a teenager, with small pieces and her poetry appearing in local magazines and newspapers, fanzines and teenage mags such as ‘Jackie’. Marrying young, she started travelling the world with my husband, had four children, worked in English broadcasting in the middle east, and became a single parent. Back in the UK, Kathleen went to university as a mature student, and wrote her first book which was picked up by Bloomsbury. Since then, Kathleen says that she has ‘almost managed to make a living as a writer’. Teaching creative writing is one of the ways that Kathleen is able to share what she loves doing most with other people. Living with a sculptor who works in Italy, she spends as much time there as she can, saying, ‘It’s a bit of a scramble sometimes – a crazy life – but I wouldn’t have it any other way.’

Once Kathleen and I got chatting, we found we had many interests in common – a love of the Lake District, photography and the influence of art and biographies on fiction to name but a few. I suggest you grab your beverage of choice and enjoy!

Welcome, Kathleen. As a keen walker, I’m envious to learn that you live in Cumbria on the edge of the Lake District. How does your home and its environment influence your writing?

I think it’s more how being brought up there has influenced me. I had a very unusual childhood on a remote farm in the hills of the Lake District without electricity or modern plumbing. With no television, people talked and told stories in the evenings – all the old farmers and their wives. I grew up fascinated by people’s lives and relationships, and the isolation (without modern media) also fostered a passion for books.

Who was it who gave you your first encouragement as a writer?

One of my teachers sent a poem I’d written off to a magazine when I was 9 and it was published. I’ve never forgotten the feeling of seeing it in print. When I was 13, I sent some of my poems off to the cousin of the historian JP Taylor (who was a poet), though why I chose her I don’t know. She wrote a lovely letter back, which I still have. It more or less said that if I was a real writer I’d keep on writing and that getting published didn’t matter all that much. She stressed that it was important to ‘work, work, work’ and practise constantly. She made an analogy with concert pianists – if you didn’t have complete control of technique, your writing wouldn’t be good enough.

You write across a broad spectrum: poetry, biographies, short stories and novels. Is a different discipline required for each?

I write in almost every discipline except drama and they all require different techniques. I don’t set out to write a particular thing, it’s just that the ideas I have develop differently – some are more suited to a poem or flash fiction, some need a longer exploration. The differences are tonal and structural. But I really enjoy variety and would hate to be confined to just one genre. I used to write a certain amount of journalism when the children were little and time was short and thoroughly enjoyed doing features for SHE and Cosmo – they took me to interesting places and included tracking down historical women, observing Glasnost, and writing about witches covens and singles’ clubs. At the same time it’s probably one of the reasons I’m not better known – I’ve never concentrated on a single genre.

Click here to buy

And as someone with such a diverse output, do you find that there are common threads running through all of your work?

Only a fascination with people’s lives – that’s what drives all my writing. And I’m interested in how people deal with difficult situations and overcome things that would defeat most of us. Katherine Mansfield was abandoned alone in Germany at 19 to give birth to a stillborn baby, and was then diagnosed with advanced TB in her twenties. Her courage and determination to write ‘in spite of all’ was amazing. Catherine Cookson was born into one of the poorest communities in the western world, into a family whose members were largely illiterate, at a time when women didn’t even have a vote, she started life in a workhouse laundry but she went on to become one of the richest and most famous authors in the world. That’s a story!

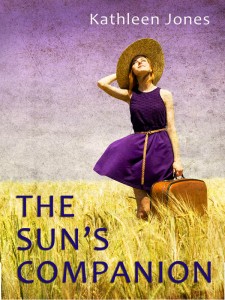

In my novels I can see that there are the same motivations – The Sun’s Companion is my mother’s story – the women who were teenagers at the beginning of the second world war, who lost all their career opportunities because of it. My mother also lost her first husband. The Centauress has two protagonists who have to survive some of the worst things that can happen to a human being. Zenobia is born ‘between sexes’ and unable to have any kind of ‘normal’ life; Alex has lost the person she loves in a terrorist attack and no longer feels that life is worth living. Life throws up terrible things, and we have to work out a way of surviving. I’m interested survival. Perhaps that’s the common thread.

I asked Kathleen to select a favourite quote about writing

I write largely fact-based fiction, and so I read a lot of biographies as part of my research. It is said that you can be more truthful in novels than you can when writing non-fiction, biographies included. (My favourite description of fiction is that it is ‘made-up truth.’) As someone with experience of both, do you feel freer when writing fiction?

I’ve always felt that a biography is a ‘found novel’ – you’re given the plot, the characters and some of the dialogue and you have to use a novelist’s skill to make the story come alive for the readers. In the same way, a novel is a fictional biography. The boundaries between the two are very fluid, but there are certain occasions when you can tell profound truths about people and their situations better using a fictional treatment. You aren’t really allowed to ‘interpret’ or create imaginary sequences of ‘how things might have been’ in a straightforward biography, though Peter Ackroyd did just that in his biography of Dickens. I also admired Julia Blackburn’s ‘Daisy Bates in the Desert’ which combined memoir, fiction and biography in order to tell the story of the nineteenth century Daisy Bates. It’s not something I’ve been tempted to do – so far!

Fiction gives me the freedom to explore the way people live their lives in any way I want to – it’s both liberating and terrifying because there are no boundaries.

I am currently reading ‘And the Mountains Echoed’ and this quote seemed particularly relevant to our discussion.

You’ve written eight biographies, most of them about authors and poets. I assume that you have discovered your subjects through their writing, but there are so many writers out there. What else draws you to your subjects?

It’s the writing that draws me in first – with Margaret Cavendish it was the voice of a 17th century writer lamenting the way she was silenced by men. With Katherine Mansfield it was her personal journals, charting a teenage compulsion to be a writer, that attracted me. There has to be empathy, and I have to find the characters interesting. It takes a long time to write a biography, so you have to be able to live with someone for a couple of years at least! Katherine Mansfield took me ten years to research and five to write.

You must feel a huge responsibility writing about real-life subjects. Do you think that your first responsibility is to tell the truth or have you ever discovered a story so personal that you have decided not to tell it?

I try very hard to tell as much of the truth as I’m allowed to know. But I also believe that the public doesn’t have the right to know everything. Living people need to be protected, but I can see no reason why the truth about the long dead shouldn’t be revealed. I’ve written three biographies of contemporary authors and there were things I was told that I wasn’t allowed to write because they affected the lives of other people who weren’t willing to give their permission. I respect that. But, if these restrictions meant distortion of a significant part of the book then I wouldn’t agree to write it. I wouldn’t want to be party to any kind of ‘cover-up’.

I studied law originally, with the intention of becoming a barrister, and I try to approach a biography like a court case – you put the case for the prosecution and also for the defence, lay all the evidence in front of the readers (who are the jury) and let them make up their minds for themselves.

I see that you have used extracts from personal correspondence in your works and have been complimented on your judicious choice of what to include. Again, when using material that was only intended to be read by its recipient, how do you decide what to reproduce?

I used to work for BBC Radio and I think the training in ‘soundbites’, catching the listener’s ear, is useful training for picking the right quotes to hold the readers’ attention. Quotes are always difficult – you just have to go for what ‘stands out’ and paraphrase the boring bits! Reading private letters for a biography always feels rather voyeuristic, but it’s also a great privilege – I once read Lawrence of Arabia’s letters to the wife of Bernard Shaw and it was a spine tingling experience.

With your poetry, you’ve collaborated with landscape photographer Tony Riley. How did that come about?

The collaboration with the photographer was a project put together for European Visual Arts Year. The idea was that we visited locations, separately and together, and he would take photos and I would write about the places we’d been to. The challenge was not to have the text as simply an explanation or description of the photograph, but in the end there was no danger of that happening! It was interesting to see how different our viewpoints were, particularly the details that caught our separate eyes, and how focusing something through a camera lens often made the image tell a completely different story. I’m really interested in this kind of ‘story-telling’.

I can see from your reviews that readers find your novel difficult to describe – “Not literary fiction, not genre fiction, almost the novelisation of modern history.” How would you categorise your own fiction, or do you prefer to see yourself as the ‘brand’.

I think I would have to be the ‘brand’ because everything I write is different. My biographies don’t stick to the traditional rules either. Katherine Mansfield was written mostly in the present tense and I used the structure of the blockbuster ‘saga’ for A Passionate Sisterhood. I have a very creative approach to genre. Classification is a retrospective thing – I’m not thinking about it when I write, though I know that some authors are. As far as I’m concerned, the genres were invented by book shops and librarians to keep books in order for ease of cataloguing – it’s the opposite of creativity.

John Irving says that you can’t teach writing. You can only recognise what’s good and say ‘keep doing that.’ More recently, Hanif Kureishi has caused controversy by being less than complimentary about his students. As someone who teaches creative writing courses, do you think John Irving is right? (My own experience of starting a Creative Writing MA was that the university was completely out of touch with the publishing industry, which, of course, you are not.)

When I’m running creative writing courses I try very hard not to be prescriptive. The emphasis has to be on the ‘creative’. I’m an ‘enabler’ – though I hate that word. You can pass on techniques and share your experience and give editorial feedback and encouragement, but you can’t teach people to write. I gave up working in University creative writing departments because of the demand that we mark students’ work on scales that took no account of innovation and originality. Quite mediocre pieces of writing could get high marks, while snippets of genius would be marked low because they didn’t tick any of the boxes. As you’ve also noticed, some universities haven’t quite caught up with developments in the publishing industry – they are still trying to feed students into the traditional, agent-led, channels. I feel it leads to a particular kind of writing – as a judge for literary awards I can recognise the ‘creative writing MA’ piece from the first few lines. There’s a self-consciousness and lack of freedom, even when the writing is very, very good.

Click here to buy

As someone who has worked within the media and whose work has appeared in a broad range of publications, do you think the media gives enough coverage to books?

Statistically the literary heavy-weights as well as the lighter periodicals are devoting less space to book reviews and critical comment than they used to do. But at the other end of the scale the internet is bursting with people discussing books, reviewing and promoting them. It’s simply shifted to a new location that empowers the reader rather than having a few literary figures pontificating about books they think the rest of us should read. This is a good situation. There was a lot of literary back-scratching in the old system (I know – I was in it) and I think the new scene is a lot healthier, despite the odd troll lurking in the undergrowth.

I was contacted by a writer last week who was concerned that I had just published the novel she was in the middle of writing. I have had similar experiences. (I was concerned that A Funeral for an Owl might be too close to Pigeon English.) I have to say that your short story Three seems to share common elements with Deborah Levy’s Swimming Home. Do you think it’s true that there are only so many stories?

That’s an interesting observation – I hadn’t read Swimming Home, but now must dash off and get it! Yes, there are only so many human situations to explore – only 7 according to Christopher Booker. On the other hand, every story is unique because the person telling it is – I think that’s why we love certain stories more than others, because they combine the familiar and the original in a compelling way.

Your latest novel, The Centauress (whcih is also your contribution to the box-set), seems to combine all of your writing experience. Its narrator is a biographer of Zenobia de Braganza, described as one of the most famous living European painters. I recently interviews Isabel Wolff about her novel Ghostwritten, in which the narrator is ghost writing a memoir. How do the two roles compare?

I’m afraid I’ve never ghost-written anything, so really can’t compare, but certainly The Centauress is based on personal experience. This is one of the reasons why my agent didn’t feel able to take it – apparently publishers don’t like books about writers, though it’s clear that readers are fascinated. By a complete coincidence, Linda Gillard’s recent novel Cauldstane is also about a biographer and also independently published. We both finished our books around the same time and I found it really strange (and just a little spooky) that we’d chosen similar subjects, though the novels are completely different.

Click here to buy

The First 50 Words

In The Centauress, the subject of the fictional biography says that she ‘wants to tell the truth now so that people can’t tell lies after she’s dead’. Did writing the novel make you reflect on your role as a biographer and do you think the writing of it will make you change your approach to writing biographies in the future?

The novel, The Centauress, came out of my experience as a biographer, trying to get at ‘the truth’ of my subject’s lives. I learned the hard way, interviewing people and then hearing them say ‘I never said that’ or ‘I never meant that’. People don’t necessarily tell the truth about their own lives. Self-deception is rampant (probably the only way we can comfortably live with ourselves!). Catherine Cookson was an author who deliberately created a version of her life story to market both herself and her books. She tried very hard to suppress anything that would contradict the image she created. But the details of her life and the truth about her past were quite different – actually more interesting. There were areas of her life she didn’t want anyone to go into. I got a lot of criticism for revealing things because her estate, her publishers and some of her fans thought the revelations ‘tarnished’ her image. But they were all true and I thought they made Catherine’s life more remarkable. In The Centauress, one of the characters says ‘Truth! Why do we value it so much when sometimes a lie can be so comforting? And so useful!’ Perhaps there are some truths that are better left untold.

I asked Kathleen to choose her favourite opening line from a novel.

Photography is a passion of mine. I have to say that you hooked me in with your reference to a portrait of Zenobia by Man Ray. In fact, it was looking at the portrait that made your narrator decide she wanted to write Zenobia’s biography. Have you ever been similarly struck by a single image?

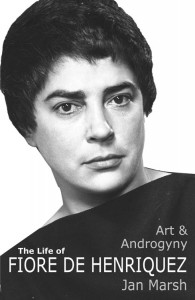

It was the image that led to the book – a haunting photograph of the Italian artist Fiore de Henriquez by Felix Fonteyn (the brother of Margot Fonteyn). I couldn’t look away. Exploring the personality behind those eyes became compelling. In The Centauress, Alex finds Zenobia’s probing eyes very uncomfortable because she has her own secret that she doesn’t want to reveal.

In your book, narrator Alex hates being asked about what she writes. I must admit to suffering a similar degree of discomfort. After answering the question, however, the person she is in conversation with concludes that she is ‘a proper writer.’ How do you think that judgement is made?

People judge you on what you’ve published and where. That remark was actually once made to me! I hope I was polite. The sub-text is that you’re only a proper writer if you’ve been published by a magazine/publisher that people have heard of. Scribbling in the attic or self-publishing doesn’t count! Grrrrrrr…… But it is the public perception and it’s one that Indie authors are having to grapple with.

Zenobia is described as a prickly character, but one of the things that she is open about from the start is that she is androgyne, both man and woman. She believes the fact that can see things from both a male and a female perspective is what makes her art unique. How difficult was it to create unique fictional works of art?

That’s an interesting question. I live with a visual artist so I get to look at a lot of art – I really enjoyed creating the kind of art that I thought Zenobia might have produced. I was influenced quite a lot by the work of Frida Kahlo and the way she painted her body and her mind – making the psyche visible. The male v female in art is very controversial at the moment and Zenobia does talk about it, but I didn’t want to get too bogged down with this issue in the novel, so it’s very lightly treated.

Although Zenobia didn’t meet Marilyn, she painted her. Reading your descriptions of Zenobia, I am reminded of the photographs of Edith Sitwell, another famous eccentric, sitting together on a sofa with Marilyn and of how much two seemingly different people found they had in common. It seemed odd in a way that two people, Edith a throw-back to another era, Marilyn very much of her time, should come together in the same place at all. I know this is really an observation rather than a question, but I wonder how you feel about it.

I loved that photograph of Edith Sitwell and Marilyn Monroe sitting on a sofa – how I would have liked to have been there to eavesdrop the conversation! On the surface Marilyn and Edith had nothing in common, but in fact they shared a great deal. They were both performers in a male dominated world and there was a deep level of insecurity in each of them – the physical persona and the performance were simply ways to hide this. This is what I believe, anyway! In the novel it was those qualities in Marilyn that attracted Zenobia to her, because she too was a performer and deeply insecure.

Seven of the most prominent female entrepreneurial authors have brought their work together in a limited edition compilation of novels — Outside the Box: Women Writing Women. The collection will be published in e-book format on February 20 (pre-orders from January 12) and available for just 90 days. Find out more by visiting www.womenwritewomen.com

‘Outside the Box is an extraordinary collection, varied in style but united in quality, demonstrating precisely why indie publishing is a treasure trove for readers.’ JJ Marsh, author of the Beatrice Stubbs series and founder member of Triskele Books

You have collaborated with six other women writers who are showcasing work with a diverse range of female heroines. How did you choose the title you would contribute?

We were looking for books with unusual female protagonists so The Centauress was the obvious choice.

Having been traditionally published, what were the key factors that influenced your decision to become an indie author?

It was a gradual process. The first was the number of books on my back-list that weren’t selling enough to motivate my publishers, but were still in demand from readers. The availability of Print on Demand made me think about putting the books out there myself, but there were quality issues with POD books, so I started investigating having them trade printed and marketing them myself. That wasn’t an easy route, but then Amazon stepped in with their ‘seller’ facility and then with Kindle Direct Publishing and using them was a no-brainer.

Publishing new books via this route took longer – I was still prejudiced against self-publishing, I’m ashamed to say.

I think that this prejudice was sold to us by people who are in the business of discouraging writers from taking that route. Certainly, at all of the writing conferences I attended, even as recently as 2012, the advice was that self-publishing was not for ‘serious writers.’

Almost losing my biography of Katherine Mansfield because of the recent upheavals in the world of publishing made me re-think this. I’d also written a novel everyone loved and which received ‘rave rejections’ from several big publishers (The Sun’s Companion). It was clear that it was more than good enough to be published, just not commercial enough to be taken on in a changing world. Everything I’d been told about good books always getting out there in the end suddenly seemed false. I put the novel up on the peer review site You Write On and it went straight into the top 5 best-sellers. Readers loved it and it qualified for a critique from Orion. The editor was very complimentary, but again didn’t think it was commercial enough for a big trade publisher. So I took the plunge into the Indie world and have never regretted it for a single moment. I’m having such fun!

Click here to buy

You have had experience of both traditional and indie publishing. How do the two compare?

The biggest differences are in response time and money. This is a typical scenario for a book submission in traditional publishing: I sent a book off to my agent (who is very good) and she passed it to a ‘reader’ who critiqued it and gave a positive report. My agent then put it in her pile to read personally – that took 6 months. The book was then sent out to publishers, who took another 8 months to read and respond – and in this case reject it. If one of them had accepted it, there would have been a further year to edit, print and publish – that’s more than 2 years from the date I finished the book. It’s ridiculous. An Indie published book can be out there in a matter of weeks while the idea is still fresh and vibrant.

There’s also a difference in the money – from a hardback book priced around £20.00 I might get £1.50 to £2.00 off every book sold. My agent takes 15% of that. On my Indie published titles I get 70% of the cover price. Even if I sell them for £3.00, I’m getting more than I would from the traditionally published titles.

Traditional publishing is competitive and cut-throat. Publishers encourage rivalry. The self-publishing arena is quite different. We help each other. It’s one of the most supportive communities I’ve ever belonged to.

You met the other writers involved in this box-set through ALLi. How did you become involved with them? Do you think it’s important for self published writers to belong to some sort of writing community?

The really glorious thing about being an independent author is that you are free to become part of this online community that has developed as a support network for the lone writer fighting their way through the self-publishing jungle. We chatter to each other on Facebook, on blogs, on Twitter and through organisations like ALLi. Some of us met through a cooperative called Authors Electric. The important thing is that we support each other.

It’s been an absolute pleasure talking to you, Kathleen. As someone who is deeply protective of her own works in progress, I almost feel guilty asking this question, but what are you working on at the moment?

A series of short stories set in Italy, in the little town I live in. There are some wonderful characters here and some of them have really interesting life stories. It’s rather like the small Lake District community I was brought up in and there’s a strong oral tradition here as well – people sit in the bars in the evening and reminisce. It’s people’s lives that

fascinate me, whether it’s biography or fiction. That’s probably the common thread that runs through all my work.

You can find out more about Kathleen and her writing on:

Website: http://www.kathleenjones.co.uk

Blog: http://www.kathleenjonesauthor.blogspot.com

Book Review Blog: http://www.kathleenjonesdiary.blogspot.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/kathleen.jones.10485

If you enjoyed this interview, you might want to subscribe to my blog. Just visit the sidebar and enter your email address.