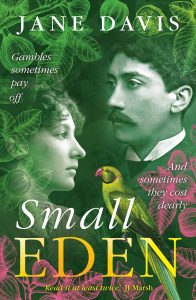

The angel in the home

The women in the cast of Small Eden who refuse to conform

Not one of the women in Robert Cooke’s circle is behaving as he expects. His wife is speaking her mind, his mother is taking herself off to Scotland of all places, his daughters are being taught science at school (science, in the name of all that’s holy!). And he’s about to discover that the winning entry in the competitive he has run for the design of his pleasure gardens is the work of a Miss Hoddy.

Extract from Small Eden

It doesn’t yet strike Robert how accurately his vision has been interpreted. The gardens took shape in his mind, and now they are here on the page. A sufficient number of alcoves and arbours to balance the long, straight rose walk. Sculptures placed sometimes in opposition, sometimes in collusion, with the placement seeming to say exactly what he wants it to say. If the designer has added creative flourishes here and there, they are entirely in keeping with Robert’s specification.

Satisfied he’s made the right choice, he gives the fire a good prod and shovels on a few celebratory lumps of coal, then summons the girls to his study. He means to show Freya he has taken note of what she said about paying his daughters more attention. “I’ve chosen the winning design,” he announces once they are assembled.

“For the gardens?” asks Ida.

“For the pleasure gardens,” he says. “Here, tell me what you think.” An invitation for them to come around to his side of the desk. He remembers the few times his own father allowed him this rare treat; when he sat in Walter’s chair, his forearms on Walter’s armrests, surveying the doctor’s domain. The leather-topped desk, the inkwell, the fine nib of the fountain pen, all at his disposal. How important they made him feel.

Estelle’s face is solemn – too solemn, he thinks, for a child her age. She doesn’t come first, as is her privilege, but pushes her sister in front, one hand on each shoulder. Her step is heavy as they arrive at Robert’s side. She wishes it to be known that she’s here under sufferance.

Immediately, Ida has her hands all over the plans, an adventurous fingertip tracing the main path. Robert fights the urge to tell her not to touch. “I should like to live there,” she says of the cottage. “Then all of this would be mine,” she says of the gardens.

“So you approve?” he asks.

Ida nods an emphatic yes.

“And you, Estelle, what do you say?”

She shrugs. Her hair has been styled in much the same way as her mother’s, parted at the centre and brushed back from her face. Instead of being piled into a bun, it has been plaited. Two titian ropes hang to her shoulders, each tied with green ribbon. “I haven’t seen the others.”

He laughs awkwardly. “The decision is already made, I’m afraid.”

“Then why ask what I think?”

Sutton High School, with its forward-thinking atmosphere, has instilled in Estelle a greater confidence in her own opinions, but this indifference cuts through him. Freya does not so much as say, Don’t take that tone with your father. Robert is on his own, his ground uncertain. “I thought you might be interested in finding out which of the gentlemen has won.”

“I haven’t met any of the gentlemen.”

She has made her point. To her, they are just a list of names. Meaningless. The moment that was supposed to be shared has dulled like a pair of spectacles fogged by a breath. Robert turns to his younger daughter: “You’ll help me, won’t you?” Ida might still polish it with a clean cloth.

A child young enough to want to please, she is owl-eyed. “What do I need to do, Daddy?”

She’s still his little girl, hair worn in ringlets, her dress smocked. “The winning design is number six. What you must do,” he reaches into his desk drawer and withdraws the sealed envelope, “is open this and read out the name that appears beside the number six.”

Ida takes the envelope, her movements reverent. She seems to understand his intention – that they share in the excitement – but struggles to get her small fingers underneath the seal.

He would like to say, ‘Here’; to break it himself. Instead, he offers her an exquisitely carved ivory-handled letter opener, something the girls have been warned not to touch, not because they might break it (it is too robust for that), but because of its value. “Perhaps you’d like to borrow this.”

“Thank you, Daddy!” Properly equipped, Ida makes short work of the task. She sets the letter opener down where Robert can reach for it and hold it close, then pulls out a folded sheet. “Number six.” She hesitates, turning to her sister. “I opened the envelope. Would you like to read out the winner’s name? You’ll do it so much better than I could.”

Robert is touched by the gesture. Ida lives in her sister’s shadow. She has so few moments to truly call her own, yet she’s prepared to relinquish this one.

“Father didn’t ask me,” Estelle answers spartanly.

Robert detects a wobble in his younger daughter’s bottom lip. If what she’s been told about the natural order of things is true, then this temporary promotion will have to be paid for. “Number six,” she repeats. Her eyes scan the page, finding their destination. “Miss Florence –”

Miss? Robert’s forehead furrows.

Suddenly animated, Estelle reaches over her sister’s shoulder to pluck the sheet from her hands. “I’ve changed my mind. I will read the name.” Ida’s expression turns to dismay; her eyes follow the sheet that was to have given her a fleeting moment of glory. “Miss Florence Hoddy.” Estelle’s expression is triumphant.

The surname is familiar, but surely Oswald was the surveyor? Robert looks to his wife, who is smiling.

“Well, well.” The first words Freya has spoken since entering the room. “Eleven entrants and you chose the only woman.”

A world on the cusp of change

In Small Eden I wanted to paint a picture of a world on the cusp of change. After the invention of the steam engine, England rapidly changed from a rural, agricultural country to an urban, industrialised one. Tremendous advances in medicine included a vaccination against smallpox, made compulsory for children by law. The publication of Darwin’s The Origin of Species had people questioning their beliefs. Great building projects were underway including Brunel’s suspension bridges and the Crystal Palace.

But despite the fact that a woman had been on the throne since 1837, British women had few rights. Writing in her diary Mrs Fawcett bemoaned, ‘I have no vote at elections, although I am a taxpaying householder and a responsible citizen, and I see that as an absurdity.’

I was proud to discover that my local town, Sutton, had a progressive high school for girls, complete with a science lab (almost unheard of at the time). Even so, the Cookes’ daughters’ access to further education would have been limited. Mill Mount College was one option. Its stated aim was ‘to prepare women to become wives, mothers, teachers and missionaries.’ A headmistress of another establishment said that she wanted the character of her school to be ‘delicate womanly refinement’.

Women were discouraged from exerting themselves physically, let alone participating in any vigorous sports. Clearly this didn’t apply to working-class women who worked harder than their menfolk, because a man’s working day began and ended at a set time, but a woman’s work in the home began when her paid employment ended. No, we’re talking about middle-class ladies, who were expected to be weak, defenceless and entirely dependent on men.

‘Women are so much more earnest about small things than men…’

That wasn’t to say that women should be idle. There were positions for them on school boards, or boards of guardians. They might raise funds for worthy causes by running charitable bazaars. They might even be parish councillors.

‘Women are so much more earnest about small things than men and parish councils deal with matters of seemingly small import.’

Mrs Barker

To give Mrs Barker her due, this might not be her firmly-held belief, but an attempt to pacify men. As one suffragist put it, ‘It does not do to call the arguments on the other side foolish.’

But it wasn’t just men who held these views. Some of the most ardent women’s rights’ campaigners thought that women shouldn’t enter the political arena. Josephine Butler campaigned tirelessly against child prostitution and pressured the authorities at Cambridge University into providing further education for women. But even she believed it would be fatal for women to be drawn into politics.

A steed upon which to ride into a new world

Then along came the big bicycle revolution.

‘To men, the bicycle was merely a new toy, another machine added to the long list of devices they knew in their work and play. To women, it was a steed upon which they rode into a new world.’

Munsey’s Magazine, 1896

Women’s rights leader Susan B Anthony credited the bicycle with doing ‘more to emancipate women than anything else in the world’. In the 19th century, bicycles became a symbol of women’s bid for freedom. Ride a bike and you could go to places where you weren’t chaperoned. Emma Eades, one of the first women to ride a bike in London, was pelted with stones and bricks. Men and women alike demanded that she ‘go back home where she belonged’. And she wasn’t alone in being attacked. The suffragist and writer Helena Swanwick reported that London bus drivers ‘were not above flicking at me with the whip’ when she cycled past and that she ‘was once pulled off by my skirt in a Notting Hill slum’.

We, the future wives and mothers of England

I have Robert and Freya’s daughters say, ‘We, the future wives and mothers of England…’ with any number of ridiculous endings, but Robert recognises that they stray very little from the nonsense popular magazines aimed at young ladies. In fact, it wasn’t just women’s magazines. Respected men in the medical field were adamant that the removal of women from her natural sphere of domesticity to that of mental labour would be ‘detrimental to the virility of the race’.

“The removal of women from her natural sphere of domesticity to that of mental labour not only renders her less fit to maintain the virility of the race, but it renders her prone to degenerate and initiate a downward tendency which gathers impetus in her progeny…”

T.B. Hyslop, Bethlem Hospital, 1905

Their mother married at seventeen and had four children. Estelle and Ida Cooke want more. And with change in the air, I have a feeling they’ll get it. They may even find support from a surprising figure – their father.

***

To buy Small Eden click here.

To have future posts delivered directly to your in-box, visit the sidebar on the right and subscribe to my blog, or to find out about new releases, competitions and freebies, subscribe to my newsletter and I will send you a free copy of my novel, I Stopped Time, as a thank you.

While I have your attention, can I please draw your attention to my updated Privacy Policy. (You may have noticed, they’re all the rage.) I hope this will reassure you that I take your privacy seriously.

Remember, if you enjoyed this post please share it.

If you have subscribed to my blog but no longer wish to receive these posts, simply reply with the subject-line ‘UNSUBSCRIBE’ and I will delete you from my list.