Inequality in the eyes of the law

Was the Ruth Ellis trial a miscarriage of justice?

My novel, At the Stoke of Nine O’Clock, is the result of a long-held fascination with one woman.

I first became aware of Ruth Ellis (pictured below) when I was a teenager. Ruth was that rarity: a female killer. ‘Six revolver shots shattered the Easter Sunday calm and a beautiful platinum blonde stood with her back to the wall. In her hand was a revolver…’ I was hooked by the story of the blonde hostess, who took a gun, tracked down her errant racing-boy lover to a public house in Hampstead, shot him in cold blood, then calmly asked a bystander to call the police.

“The traditional female role is a nurturer, not a murderer. Extreme violence is far more alien to females than to males.” ~ James Alan Fox, criminologist

Women, as we know, are far more likely to be victims rather than killers. (Arguably, the two are not mutually exclusive.) Unlike their male counterparts, women who kill tend to know their victims. Statistics also show us that women kill for very different reasons than men. Either they feel threatened (in self-defence or occasionally when they have been rejected), they carry out what they believe to be acts of mercy (predominantly relating to young children, in the belief that death is in the best interest of the child), or they intend to take their own lives and can’t bear the thought of leaving their children behind.

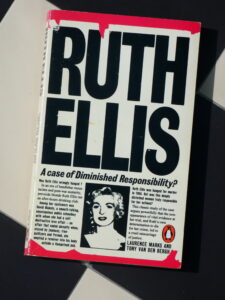

The other fact that drew me to Ruth is that she was the last woman in Great Britain to be hanged. It was after making this discovery that I first read, Ruth Ellis: A Case of Diminished Responsibility by Laurence Marks and Tony Van Den Bergh. Published in 1977, the book’s title is provocative, referencing the partial defence of diminished responsibility that was introduced in 1957, as a result of the public outcry that followed Ruth’s death.

Ruth’s case is often cited as an example of a miscarriage of justice. While I completely sympathise, I must beg to differ. Given that, at the time, the only defence to murder was provocation, given that Ruth had handed herself in and admitted her guilt, given that she didn’t want certain facts to be revealed in court (that her ‘other lover’ Desmond Cussen not only gave her the gun that she used to shoot David Blakely but taught her to shoot, and her medical history, being just two examples), how she jeopardised herself in court, and the directions the judge gave to the jury, I struggle to see how they could have arrived at a different verdict. Not forgetting that Ruth herself had repeatedly said that she didn’t want to live.

“Ruth admitted – she actually said this – that she’d had a peculiar idea that she wanted to kill Blakely. She used those words in court.”

At the same time, I have absolutely no doubt that Ruth was pre-judged. Her sex, her looks, the fact that her lifestyle was considered to be immoral (having two lovers while her divorce was not yet finalised, at a time when 73% of women polled said they thought sex outside marriage was wrong). Class also came into it. Shouts of ‘common tart’ were heard as she entered court number one at the Old Bailey, where people had paid upwards of £30 for a seat in the public gallery. And for these very same reasons, I believe she was made an example of.

Why? Because not one but two women were sentenced to hang in July 1955. Ruth’s executioner was also supposed to have had an appointment with Mrs Sarah Lloyd at Strangeways, Manchester. Mrs Lloyd (married, middle-aged, teenage daughter) had been convicted of beating her 86-year-old neighbour to death with a spade. Apparently the pair had had a long-standing feud, although the detail is lost.

Thousands of people signed petitions asking for the death penalty to be lifted in Ruth Ellis’s case, including 35 members of London County Council who delivered their plea to the House of Commons. But Sarah’s Lloyd’s case attracted virtually no publicity – the Secretary of State was under no pressure from the public to grant her a reprieve, and yet that’s exactly what he did.

Was Ruth Ellis’s crime any worse than Sarah Lloyd’s? No (unless we consider the life of a 25-year-old man to be more valuable that the life of an 86-year-old woman). It was Ruth’s failure to meet standards of conventional morality that proved fatal for her.

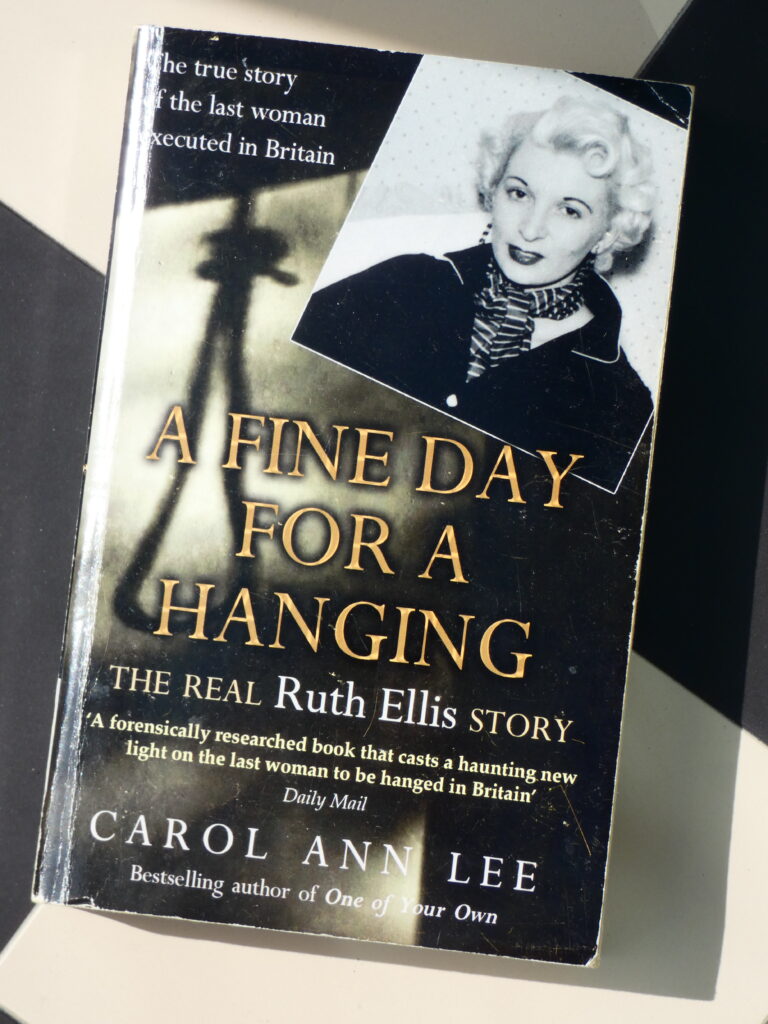

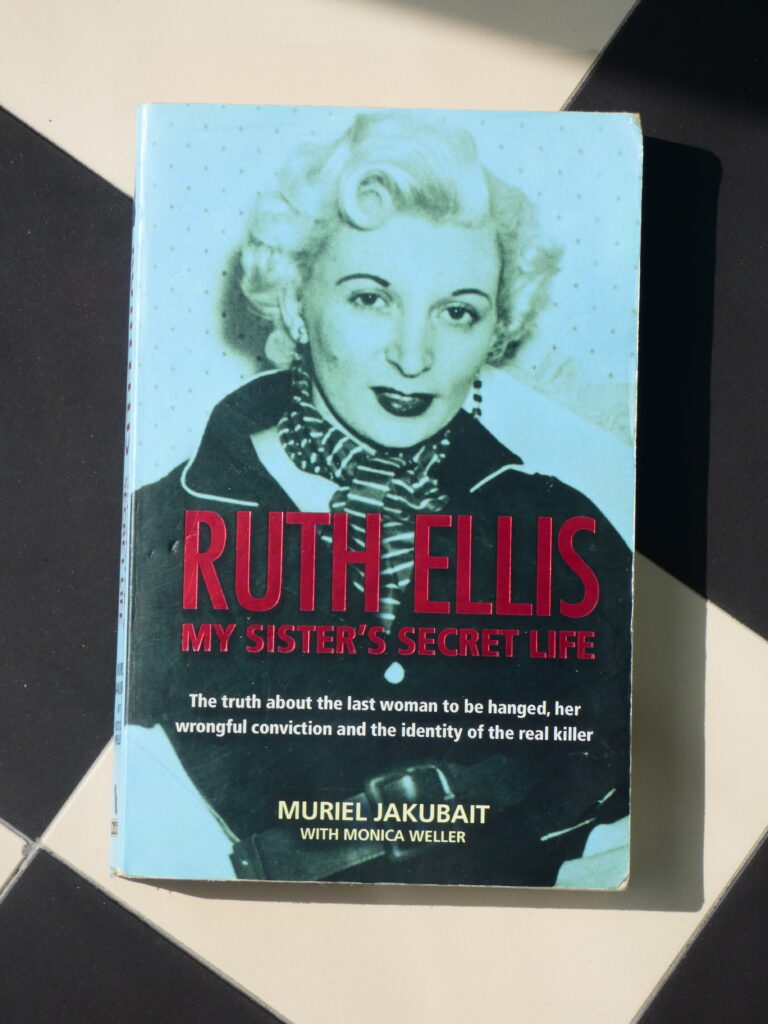

The public outcry that followed Ruth’s execution eventually led to the abolishment of capital punishment in the UK. She was, after all, a mother of two. But the full extent of the abuse she experienced throughout her life didn’t come to light until her sister published her story in 2005.

“Women who are violent are monsterised by the system.” ~ Harriet Wistrich, human rights lawyer

And so we return to the provocative book title and the question that is often asked: Had the partial defence of diminished responsibility been available to Ruth, would she have been convicted of the lesser charge of manslaughter? I wish that the answer would be yes, but to explore how Ruth might have been treated in twenty-first century Britain, we must find a ‘similar’ case – one in which a woman was driven to breaking point (and I have absolutely no doubt that Ruth was).

The case of Sally Challen (2010/11) offers a number a parallels. Like Ruth’s, Sally’ story made scintillating headlines. Middle-aged woman in middle-class Surrey bludgeons husband to death. Like Ruth, Sally took the weapon – a hammer – in her case to her former marital home, suggesting that her actions were pre-meditated. Sally also attacked an unarmed man, and was portrayed in court as a jealous woman out for revenge. After all, she herself admitted on film that if she couldn’t have him, she didn’t want anyone else to.

But despite the availability of this defence, Sally was convicted of murder. Once again, the law failed to get to the truth. When Sally’s brothers, aware that their sister had suffered at Richard Challen’s hands (and they didn’t know the extent of it), challenged why the matter of their brother-in-law’s behaviour wasn’t raised, they were told, ‘Speaking ill of the dead doesn’t go down well with the jury’, a sentiment echoed by the Crown Prosecution Service’s representative: ‘It’s not Mr Challen who’s on trial. The fact that someone was incredibly cruel and abusive towards their partner is not on its own a defence to murder.’

“The law doesn’t work well for women in relation to issues of violence. If a woman fights back, they are often punished more severely than a man that’s violent.” ~ Harriet Wistrich, human rights lawyer

That an appeal will be allowed by the courts is by no means guaranteed. Justice for Women fought for six long years on Sally’s behalf. The fact that evidence that had been available but had not been presented at trial wouldn’t be a good enough reason. The court must be satisfied that some substantial new evidence has come to light. Sally’s case rested entirely on whether the court would accept new medical evidence confirming that she’d been suffering from a previously undiagnosed mental disorder, something that may have been masked, because she drank heavily. The reason for her new diagnosis was the psychosis she suffered while under observation in prison. It was accepted her husband’s coercive control (behaviour that was only criminalised in 2015) amplified the disorder, providing the missing explanation for what appeared to be a ‘bizarre act, out of the blue’. Having already spent nine years behind bars, an appropriate term for the lesser offence of manslaughter, Sally Challen walked free.

If you want to know more about Ruth Ellis, you might like to watch The Ruth Ellis Files: A Very British Crime Story that is currently being repeated on BBC4, or click here to watch The Harrowing Case of Ruth Ellis, The Last Woman to Be Hanged in the UK on You Tube.

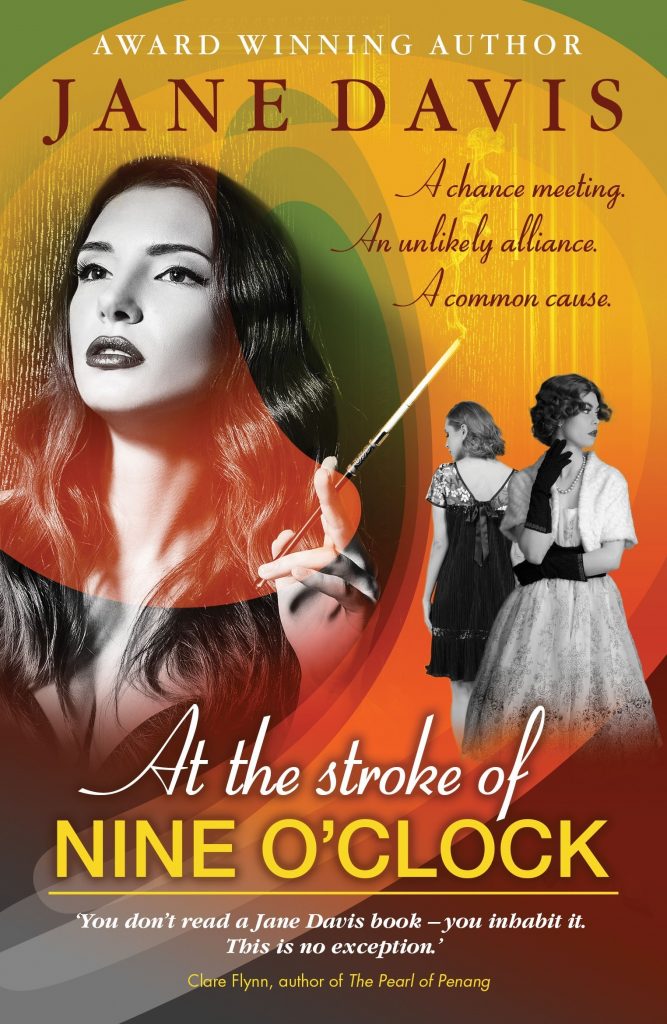

Or you may like to try At the Stroke of Nine O’Clock, which explores some of issues Ruth faced.

Click here to buy

Read a preview here

At the Stroke of Nine O’Clock

‘Before the reform of an archaic legal system, before second-wave feminism, before the #MeToo movement, the idea that the future is yours to make as a woman is an illusion.’ ~ Book Witch ⭐️ ⭐️ ⭐️ ⭐️ ⭐️

London, 1949: As the city rebuilds from the ashes of war, three women from vastly different backgrounds find themselves navigating a world dominated by men.

Like most working-class daughters, seventeen-year-old Caroline Wilby is expected to help support her family. Far from home and alone in a strange city, she must grab any opportunity that comes her way. And so she accepts a job as a hostess in a discreet gentleman’s club.

Star of the silver screen Ursula Delancy is no stranger to scandal, having left her husband and daughter to follow her lover to Hollywood. The affair almost destroyed her career. Now, desperate to reconnect with her estranged daughter, she has returned to London to appear on the West End stage. But while her performance garners rave reviews, a devastating revelation ensures that her private life dominates the headlines.

Patrice Hawtree was once the most photographed debutante of her generation. Childless and trapped in a loveless marriage, her plans to secure the future of her ancient family home are about to be jeopardised by her husband’s gambling addiction.

In a world that tries to dictate their choices, these women forge their own paths, finding unexpected strength in each other along the way. But when they unite to defend a young woman condemned for a crime of passion, they’ll be forced to confront their own deepest truths.

“Why do I feel an affinity with Ruth Ellis? I know how certain facts can be presented in such a way that there is no way to defend yourself. Not without hurting those you love.”

‘An extraordinary historical novel, so rich and detailed you emerge feeling as if you’ve just watched a classic film.’ ~ JJ Marsh, author

‘You don’t read a Jane Davis novel – you inhabit it. This is no exception.’ ~ Clare Flynn, author of The Pearl of Penang

‘This is the first time I have come across this author, and what a revelation! Jane Davis writes stunning prose that keeps the pages turning.’ ~ Historical Novel Society, Editor’s Choice

‘Another triumph from indie author Jane Davis in this gloriously gritty novel that engages head-on with a post-war London struggling to re-boot itself and wider society.’ ~ BurfoBookish

‘I didn’t so much read as consume this book.’ ~ Vivienne Tufnell, author

‘You are in the sure hands of a mistress of the written word.’ ~ Alison Morton, author

‘One of the best books I’ve read this year.’ ~ Denny