Sutton Literary Festival, Part Two

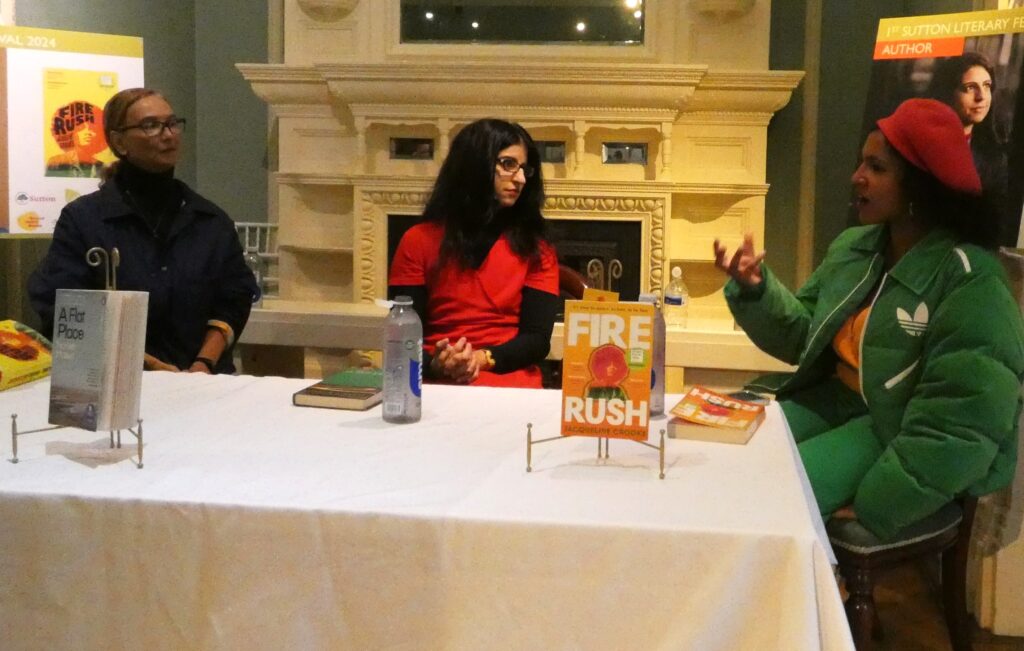

Noreen Masud and Jacqueline Crooks interviewed by Adita Jaganathan

Adita began her introduction by explaining to the audience that although the authors’ books might seem very different, both reach the same place as music, exploring memories, longings, identity and place.

Noreen Masud was born in Pakistan, a country whose boundary had been shaped by colonialism. When Britain granted India independence, it partitioned the territory it had ruled over, resulting in the displacement of 15 million people. (Aside: If you want to explore Partition, I recommend Radhika Swarup’s novel, Where the River Parts.)

Masud is a lecturer in twentieth century literature at the University of Bristol, and an AHRC/BBC New Generation Thinker. Her memoir, A Flat Place relates the childhood trauma she described as ‘dehumanisation’ and which ending with her father disowning her just before she reached her sixteenth birthday. Masud has a diagnosis of complex PTSD, the result of living with a frightening situation from which she felt there was no hope of escape. But escape she finally did, coming to Britain in 2007.

Masud described the disorientation of feeling that she is real but the world isn’t; the sense that the present is no more real than the past or the future. Hundreds and hundreds of events have lowered her understanding of what is normal. A strong sense of displacement and exile remains with her. The only person of colour in her school, she experienced the feeling of constantly being chased home.

Flat places such as Morecambe Bay, Orford Ness and Orkney have become landscapes to exorcise ghosts. In stark scenery Masud explores the stories of those who live and work there. Morecambe Bay’s cockle pickers and the migrant workforce harvesting produce in the Fenland farmlands are reminders of the still-too colonial world.

How did she arrive at the decision to write a memoir and make public extremely personal issues? Masud related something a professor told her. There is an idea that traumatised people don’t know how to tell their stories, but the truth is that the audience would not be able to cope with their pain.

“If I could make it tangible,” Crooks agreed, “I could believe it.” She chose fiction as a vehicle to explore her own truths. Masud replied that she could not have written a fictionalised account, because with fiction there has to be a beginning, a middle and an end. She still has no explanation for the pivotal scene in her life. Instead, she has had to learn to cope and live with things she doesn’t understand.

A Flat Place is her answer, a combination of nature writing and memoir. Yet any decision to write about your own life is fraught with ethics. People do not live in isolation. Her father, she told us, is dead and she does not believe that she owes him anything. But what of other family members? Masud asked herself what is the cost of speaking versus the cost of not speaking. Though it was painful for her mother to read, Masud said that you can never predict how people will react. They are now far closer because their relationship is now authentic. But, she said, you can never return to the person you were.

Adita asked Crooks to talk about the play with time that she found of every page of Fire Rush. Born in Jamaica, the idea that the past is very present in the here and now comes naturally to Crooks. She was

brought up with the idea of drawing on the spirit of her ancestors, of the dead who use dreams to send signals and signs to the living.

Crooks’ novel celebrates an underground dub reggae club scene that mainstream culture had no idea existed. The world Crooks wrote about is lost to all but those who lived it. You can hear Jacqueline talk about dub reggae and its origins here.

Her journey to publication began over a decade ago. Her then literary agent urged her to tone back her use of patois, but this only cemented her vision of what the book’s rhythm could – and should – be. Numerous edits followed. Crooks’ desire for authenticity paid off. When she re-submitted the book, time appeared to be her side. The literary landscape had changed, with publishers actively seeking out books that articulate lived experience. Since publication, Fire Rush has won the Society of Authors Paul Torday Prize and been shortlisted for the Women’s Prize for Fiction, the Waterstones Debut Author Prize, the Jhalak Prize, and the McKitterick Prize. She was also named as one of The Guardian newspaper’s 10 best new novelists in 2023.

Honesty involves writing about people who have had an impact on her life. To get as close to the truth as possible, Crooks said, you must be fearless. While she is not Yamaye of the novel, Yamaye’s story is based on Crooks’ life experiences. Yamaye finds escape from her broken family home at The Crypt, a makeshift club, where she too finds freedom.

Sound, Crooks said, is a superpower that cements us in the past. Music compelled her body to move. Fire Rush is set in 1970’s and 80’s Britain, a time of race riots, among them the Southall uprising of 1979. Dub reggae was the sound of revolution. Writing the book in stolen hours at four or five o’clock in the morning with dreams still within grasp was to return to that era and the sense of freedom that can only be found on a dance floor.

To have future posts delivered directly to your in-box, visit the sidebar on the right and subscribe to my blog, or to find out about new releases, competitions and freebies, subscribe to my newsletter and I will send you a free copy of my novel, I Stopped Time, as a personal thank you.

While I have your attention, can I please draw your attention to my updated Privacy Policy. (You may have noticed, they’re all the rage.) I hope this will reassure you that I take your privacy seriously.

Remember, if you enjoyed this post please share it.

If you have subscribed to my blog but no longer wish to receive these posts, simply reply with the subject-line ‘UNSUBSCRIBE’ and I will delete you from my list.