I must admit that ‘I Stopped Time’ was not my original title for my story of how Sir James Hastings discovers the mother he never knew through her body of work. However, reading accounts of pioneering photographers, it soon became apparent that it was the phrase that best expressed most photographers’ feelings about what it is they do.

Searching on Google, I noticed that Brian Clegg’s biography of Eadweard Muybridge is sub-titled, ‘The Man Who Stopped Time.’ The real question – one of those posed by my novel – is:

Why might you want to stop time?

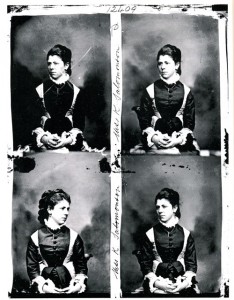

The featured photograph on this post was taken at the photo booth outside the entrance of Wimbledon station a month after my eighteenth birthday. I may look very serious, but in fact this was a declaration of independence. I was about to apply for my for my first individual passport, so that I could go on holiday with my then boyfriend. My parents were understandably nervous.

In Muybridge’s case – a man whose life was stranger than any fiction – he wanted to stop time in order to provide the scientific proof to settle a long-standing bet, which he succeeded in doing with a single negative. Speculation had raged for years over whether all four hooves of a horse left the ground when it was galloping. Californian Governor, Lee Stanford believed they did, but this motion was too fast to detect with the human eye. In 1872, Muybridge began experimenting with sequential photographs using 12 cameras, a process which paved the way for the moving pictures (His sequential photos were animated in 2006). During one of his frequent absences from home, Muybridge’s young wife, Flora, had an affair with drama critic, Major Harry Larkyns. Believing that Larkyns was the father of his recently born son, Muybridge tracked him down, and shot him point-blank. At his sensational murder trial in 1875, several witnesses testified that Muybridge’s personality had changed after he suffered a head injury in a runaway stagecoach accident. The jury threw out Muybridge’s defence on the grounds of insanity (his plan to kill Larkyns was clearly pre-meditated and had first involved tracking him down), but he was acquitted on the grounds of “justifiable homicide.”

Click here to buy

Within a generation, having a portrait taken has gone from something reserved for special occasions – an engagement announcement or an appointment to the board of directors – to an everyday occurrence. My father-in-law’s first job involved photographing the dead. Ship-building was still one of Liverpool’s major industries and the town was a magnet for immigrants. After people died it was customary to send a photograph of them to their loved ones at home. If none could be found, corpses were dressed and made-up, posed and photographed. This was considered a suitable job for a fourteen-year-old school leaver.

Neither of these purposes applies to my characters. When Lottie Pye first puts the question to Mr Parker, he gives her an answer that you might expect an adult give to a child. Not a lie, but certainly not the whole truth.

A world on the brink of change

Disappearing underneath a black shroud, Mr Parker adjusted the height of the box, bringing the viewfinder down to my eye-level. Holding up the veil, he commanded, “Look through here and tell me what you can see.”

I caught my breath, stood back in wonder, and looked for a second time: “Everything! I can see everything!”

“This…” He might have winked. “…is my time machine.”

“It’s a camera,” I insisted.

“No, no.” He shook his head, absolutely serious. “My eye sees the image. That should mean I’m the camera. This device simply allows me to stop time.”

Too old to be teased, I folded my arms tightly. “That’s not magic. It’s science.”

“So cynical? You’ll never convince me what I do isn’t magic.” His disappointment in my inability to appreciate this was evident. “All I need is light, chemicals and a little patience.”

“Why would you want to stop time?”

“Now that is an intelligent question!” Mr Parker pressed both index fingers to his lips as if in prayer and, averting his gaze, paced a few heavy steps. When he turned back I detected a darkness in his eyes that had not been present before. “Can you think of a really good memory? Perhaps you can see it when you close your eyes. Now, imagine you could take it out and look at it whenever you wanted to.”

The advantage obvious, I nodded enthusiastically.

“And if I’m really lucky – if I’m there at just the right moment – I might capture something astonishing. The birth of a new century. A world on the brink of change.”

Of course, the pioneers of photography did those things too, but my interest is in their psychological motivation. I was delighted when one American reviewer wrote, ‘This book voiced everything I’ve held inside of me as a photographer. Stopping time…looking at the world with a different perspective. I found it to be affirming of all artists, especially photographers.’

This article contains some wonderful examples of frozen moments in time.