Last week I saw a blog post by S J Huang mourning how writers’ desire to make fictional women somehow unobjectionable can flatten out everything that makes characters the most compelling.’ Warning: this link comes with a language alert.

It isn’t helpful that much on-line advice on character development – and this was written by a woman, I might add – suggests that writers focus on their male characters. And I quote: “While a good heroine is vital to the story, the hero is even more important.”

Generally, it seems that male protagonists are given licence to be uncomfortable and difficult, but their female counterparts must fall into the camps of earth mothers or kick-ass feminists.

I asked my fellow Boxsters, “Have you ever felt under pressure to make your female characters likable?”

Joni Rodgers: When I was searching for a publishing home for Crazy for Trying, I got a lot of feedback (in the form of rejection letters) positive about my main character, Tulsa, who is overweight and encumbered by body issues. But agents and editors had a problem with Tulsa’s mother, Alexandra, a lesbian who has died, cutting Tulsa out of her will, at the opening of the story. Alexandra and her longtime partner, Jeanne, have the audacity to wish they were married. In the 1970s setting of the story, of course, that’s not possible, and in the 1990s, agents and editors kept telling me to cut that storyline because it was off-putting or even offensive to readers. I felt it was important, because the soul of the story is about that orphaned feeling that comes from being different, being told we don’t fit it and that who we are is intrinsically wrong.

A lot has changed since MacMurray & Beck (now MacAdam-Cage) first published Crazy for Trying in the late 1990s, but I think a story about disenfranchisement and how we all search for that home of the soul is always going to resonate for a lot of readers. Certainly, a story about two women who want to marry and raise the daughter they both love—what happens when the biological mother dies and her longtime partner has no legal standing—is a story that still needs to be heard as the fight for marriage equality continues. The opportunity to bring Crazy for Trying “out of the vault” as an indie gave me a chance to revisit the manuscript, trim some of the stuff I added back then under pressure to make the women in the book “more approachable” and restore the original storyline about Tulsa’s relationship with her two moms. I think the updated edition is as readable and entertaining as the version published by MacAdam-Cage, but this shorter, faster paced version clears the way for the characters to shine in all their stubbornly imperfect moonglow.

Roz Morris: When I wrote Carol, the narrator of My Memories of a Future Life, I saw a person who was probably not likable on first glance. We meet her in a yoga class, which has made her incandescently bad-tempered. Back home, she is staggeringly rude to her best friend’s new boyfriend. But that’s the surface. Inside she is grappling with a horrifying fear. She’s a concert pianist with a mysterious injury that stops her playing, and she’s terrified this will be permanent. She’s angry with the world for not being as special as her time with the piano. She’s angry with people who find it easy to fit in, to woo lovers, to be alive and contented. She believes she fits nowhere – because the piano is the way she has filled her life with love. This is the core of the story, and on this level I felt a deep comradeship with her. Carol takes the journey of everyone who might lose the thing that keeps them alive.

But books reflect society. Why has this question been asked? Indeed, should it be this – are women expected to have different modes of behaviour than men? If a man behaved in an ‘unlikable’ way – whatever that means – would that be more tolerated than if a woman did the same thing?

Carol Cooper: My characters are inspired by real life. As a doctor, I come into contact with a Chaucerian range of people. Of course I can’t put real patients (or colleagues) into a book, but I can’t help being affected by their triumphs, their tragedies or just their little foibles.

That’s why the characters in my fiction are so complex and flawed. They break a few laws, make poor career choices, and sleep with all the wrong people, but they’re kind to children and animals so they’re basically decent. I didn’t set out to make the characters likeable, but I always have to care about the people in books that I read. Unconsciously I must have obeyed the same rule in my writing.

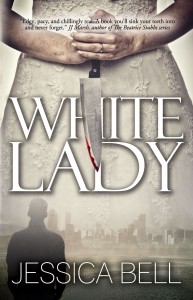

Jessica Bell: I’ve never understood why there is such an obsession with “likable” characters. What does that really mean anyway? Isn’t it more about being able to “relate” to the characters in some form or another? I don’t go out of my way to make my characters “unlikable,” but it’s something I am often criticised for. All I know is that I make my characters as real as possible. If someone is a murderer, I’m not going to force them to be likeable just for the sake of it—I’m going to make them do the things they would do naturally. If being nice about something comes naturally to them in a certain situation, then so be it. And if readers like them for it, that the reader’s perception, not my preconceived intentions.

Sonia Shâd, who is the wife of a drug lord in White Lady, has an obsession with blood and slicing people’s throats. On the surface she is not a nice woman. She is a criminal and gets off on watching people die. But she is also a mother who loves her son and would do anything to protect him. Even when it means attempting to give up the criminal activities that help her live and breathe. No, she is not a likable woman, but she is definitely a woman that you can relate to. Who wouldn’t do the best they can for their kids? Love is such an innate emotion. When there is love, everything else seems to fall into the background. And take Dexter for example. He is a monster. Yet, readers and viewers of the TV series fell head over heels in love with him. A serial killer for goodness sake! I don’t see any reason why we shouldn’t feel the same way for a woman in a similar role. Unfortunately, society seems to be more critical of unconventional women. I hope this box set will begin to change that.

Kathleen Jones: My female protagonist, Zenobia de Branganza, is based on a real person – a woman I met in Italy fifteen years ago, who was one of the most amazing people I have ever known. She was outrageous, flamboyant, mesmerising, and didn’t care what anyone thought of her. I wanted to write about her from the first moment I knew her. In the novel, Zenobia, like the woman she is based on, is a hermaphrodite – part woman part man – which is just about as unconventional a heroine as you can get. It’s been such a taboo subject that, when I began my research, I was surprised to find that as many as one in two thousand babies are born every year with some kind of gender anomaly, though true hermaphrodites are rarer. Living between genders, or ‘intersex’ as it’s sometimes called, can be tough. The woman I knew had been through some very hard times and it had affected her personality in a negative way. She could behave appallingly, but she had such charisma people usually forgave her. The character I’ve created is softer than the original – rather less edgy and egotistical. But I didn’t want Zenobia to be too likeable – she is selfish and damaged and has caused emotional chaos in the lives of those who loved her – what her companion, Freddi, calls ‘the heaven and hell of living with Zenia’. You may love her – you may hate her, but you can’t ignore her!

For myself, I come from the school of thought that thinks that people in general don’t fall into two distinct camps. They are not either ‘likable’ or ‘unlikable’. I only meet my characters when they are under immense pressure, and whilst pressure can create heroes, sometimes it forces ordinary people to do terrible things. I am also a firm believer that perfect people aren’t all that likable. Be honest. When someone appears to be too perfect, do you gun for them? Of course you don’t. You can’t for them to fall flat on their faces.

One example of this is the character of Ayisha from my 2012 novel A Funeral for an Owl. One of the main characters, Ayisha is a rigid rule keeper. You might think that a respect for rules would be acceptable in a high school teacher, but some readers thought her cold. They far preferred my rule-breaker, Jim. Why is it that rule breakers are so interesting? Because we can recognise their humanity. We may recognise ourselves, or the people we’d like to be, if only we were a little braver.

And so, in An Unchoreographed Life, in a highly competitive environment, I allow my main character Alison her flaws. She makes a calculated seduction of an older man in order to further her career. She judges the man who first offers money for sex, and then accepts his offer. She shuns a friend who points out some inconvenient home truths. She is a poor judge of character, mistaking kindness for weakness, thinking unkind thoughts about another woman because of her size and the way she dresses. And, at the same time, she’s drawn towards the person who turns out to be a manipulative character because she’s attractive and well-dressed.

My job was make readers identify with Alison. To ask themselves ‘What would I have done in the same situation?’ I did this by trying to show her flaws as scars that life has left on her. And by never letting readers doubt the magnitude of the love she has for her daughter.

If we, as a group have avoided writing conventional female characters, what makes others fall into the trap?

“Game of Thrones” author George R.R. Martin has been praised for his ability to write believable, three-dimensional female characters. Asked what his secret is, he replied, “I’ve always considered women to be people.” It seems so simple.

I hate to say it, but my favourite female fictional character of recent years has been Stella Gibson from the television series, The Fall. She is so complex that, at the end of series two, we still feel that we are only just getting to know her. And the reason I hate to admit to this? Stella was created by a man.

While mainstream publishing plays safe with predictable heroines who repeat the same familiar tropes, I wonder, does it expect the same from its female authors?

Perhaps this is where being indie differs. The only question we need ask ourselves is What is right for the book?

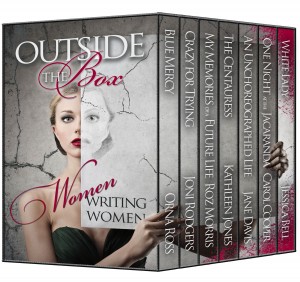

Outside the Box: Women Writing Women is an unapologetic celebration of female characters, with no attempt to plaster over the flaws that make characters compelling.

Our diverse cast of characters include: A woman accused of killing her tyrannical father who is determined to reveal the truth. A bookish and freshly orphaned young woman seeks to escape the shadow of her infamous mother—a radical lesbian poet—by fleeing her hometown. A bereaved biographer who travels to war-ravaged Croatia to research the life of a celebrity artist. A gifted musician who is forced by injury to stop playing the piano and fears her life may be over. An undercover journalist after a by-line, not a boyfriend, who unexpectedly has to choose between her comfortable life and a bumpy road that could lead to happiness. A former ballerina who turns to prostitution to support her daughter, and the wife of a drug lord who attempts to relinquish her lust for sharp objects and blood to raise a respectable son.

I’m going to let Roz Morris have the last word: “When I mentor writers, I see a lot of discussion about whether the reader will like our characters. I find the term ‘likability’ is misleading. Many perfectly compelling novels feature a protagonist who is deeply flawed, badly behaved and a person to avoid in real life. But fiction is different. It lets us indulge our curiosity in a safe space. So main characters don’t necessarily have to be people we’d approve of, rely on, confide in or matchmake with our best friend. What they actually need is this: a grain of humanity that attracts our interest, a vulnerable hole that might threaten us all.”

Want more information? Visit www.womenwritewomen.com

Watch our video trailer

Order now on Amazon.co.uk or Amazon.com – but remember, it’s only available for 90 days!

Tweetable headlines

7 unforgettable books by award-winning #WomenInLiterature. Only $9.99! Avail. Only 90 days! http://goo.gl/D1fyqW #WomenWritingWomen

7 genre-busting #novels in a limited edition box-set. Avail. Just 90 days! http://goo.gl/D1fyqW #WomenWritingWomen #creativewomen

Stories brimming w- passion & courage that push the boundaries. Avail 90 days only! #WomenWritingWomen #WomenFiction http://goo.gl/D1fyqW