Today’s offering is a very special edition of Virtual Book Club. Earlier this year, Vine Leave Press invited me to judge a competition of vignettes. One of those vignettes was called The Walmart Book of the Dead and my guest today is its author, Lucy Biederman. It’s an opportunity for me to congratulate Lucy on both the competition win and the subsequent publication of her book (I’m going to take the liberty of referring to it affectionately as ‘Walmart’). But first, let’s get the formal introductions out of the way…

Lucy is a lecturer in English at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio (USA). She holds a Ph.D. in English from the University of Louisiana-Lafayette and an MFA in creative writing from George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia. Prior to winning the 2017 Vine Leaves Press Vignette Award, she had written four chapbooks of poetry, and her short stories, essays, and poems have appeared recently in Bat City Review, The Collagist, AGNI, Ploughshares, Web Conjunctions, and Pleiades. Her scholarship, which has been published in The Henry James Review, Women’s Studies, and Studies in the Literary Imagination, focuses on how contemporary American women writers interpret their literary forebears.

Before I ask Lucy my first question, I want to share an extract from my judging notes with you, in the hope that you’ll be able to detect my excitement and curiosity about the author!

“Oh my goodness, it’s hard for me to say just how much I loved this piece of writing. The title alone told me this was going to be high concept, and as I read the index, I thought this is either going to be very very good or very very bad. What was I letting myself in for?

What I got was a darkly comic observational piece about the gods and scourges of the 21st Century, starting with consumerism set in a quasi-surreal and only slightly alternative Walmart. ‘Spells’ touched on dysfunctional relationships, living with post-traumatic stress disorder, living life vicariously through a screen, gun control, climate change, brainwashing, social media, misplaced sense of entitlement, shoplifting, homelessness, and trying to be good in a world where caring is seen as a weakness. All while relying on a Disney Wedding board on Pinterest or an advert for tampons as illustrations!

As I read on, I both did and didn’t want to look up The Tibetan Book of the Dead. And I both did and didn’t want to know how this project started out. At the back of my mind I had a nagging fear that I was being taken for a ride – but it was a ride I wanted to go along with.”

Q: Lucy, have you always felt driven to write or was there a particular trigger?

Yes. By which I mean, I have always felt driven to write, and what I write is often in response to a particular trigger. With The Walmart Book of the Dead, some part of me had already begun to draft the book before I knew I was writing it, in the freewriting I did while I was working on my Ph.D. dissertation in Louisiana. But the trigger came during the 2016 presidential election, while I was listening to the popular political podcast, Chapo Trap House, that my brother and his friends host. They were interviewing a journalist who had done a piece on poor, rural Americans who voted for Donald Trump, and he said something like, this isn’t really a story for journalism—it would be better explained through fiction. It suddenly struck me with great force all the American-ness that doesn’t make it into American creative writing. I thought, have I ever read a book of fiction or poetry with the word “Walmart” in it? I couldn’t come up with one.

Q: And why is it that you write?

Because I read. It’s a way to be in conversation with the writers who have helped form the way I think and live, from Roland Barthes to Dorothy Allison. Jonathan Franzen talks about reading as a way to be alone with one’s ideas in a world that really doesn’t want you to be, because what are you going to buy when you’re alone with your ideas? Reading captured my heart and mind earlier in my life than writing did, but I discovered writing pretty early as a way to be even more alone with my ideas—to build a fuller world out of that alone-ness.

Q: Who gave you your first encouragement?

I grew up in a community of books and reading and writing, in the neighbourhood where the University of Chicago is. Both my parents were huge readers. I wasn’t an early reader, but I wanted to learn to read so that I could sit on the couch and read quietly like they did. I remember trying it with the Cat in the Hat, but I couldn’t get the sounds of words to stay in my mind—I was reading them out loud, very slowly and loudly sounding them out, and my parents kept flashing me looks over their New Yorkers. My dad was a lawyer, but he read more and knew more about books than any professor I’ve ever had. In my second grade class, we learned about journals and diaries, and that inspired me to keep a journal at home. I wrote in it every day, for years and years. My parents were excited at the idea of me being a writer. Both my brothers are writers, too, which probably isn’t a coincidence.

Q: Have you had any rejections that have inspired or motivated you?

Throughout my writing life, I have often encountered extremely negative reactions to my work. The most negative and life-altering of those encounters, I still can’t even talk about. It may sound strange, but it would be vanity on my part to think these reactions to my work have anything to do with my work! Sometimes one’s writing, or one’s person, becomes a mirror for certain people, and they’re looking at themselves when they look at you. They project at you with all the force they have, no matter if you are a child or if they barely know you. That’s one part of being a writer I don’t like at all. It has not inspired or motivated me as a writer—but it has motivated me as a pedagogue. As bell hooks says, as a teacher, you have a responsibility to your students to be a self-actualised person. Or else you could really cause them harm.

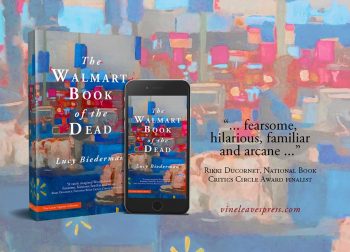

A darkly comic incantation on the gods and scourges of the 21st century. The Walmart Book of the Dead was inspired by the ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead, funerary texts with accompanying illustrations containing spells to preserve the spirit of the deceased in the afterlife.

A vastly imagined Wonderbook – fearsome, hilarious, familiar and arcane – in which a brilliantly savaged Walmart, both a temple and a tomb, spawns an epidemic of pharonic proportions, exhausting nothing less than everything. An extraordinary experience. ~Rikki Ducornet, author of The Deep Zoo and Brightfellow

Click here to look inside or buy

Q: Did you incorporate any real life characters into your writing? If so how?

Yes. I stuffed into this book a lot, maybe most, of what I’ve ever heard or experienced in or around Walmart. When I realised Walmart would be the site of this book, I found I knew dozens of stories from my own life, and stories people had told me, about being there, working there, things that had happened there. As I wrote about some of the people I had seen or known or observed, they became more real and sympathetic to me than they were in real life. I know them better now, having written them.

Q: What is your favourite novel which has a writer as one of its main characters? And what advice have you taken on board from that character?

I’m cheating here, because this is an essay, not a novel, but in The Art of Fiction, Henry James writes of “an English novelist, a woman of genius,” who glances through an open door and, from what she sees there, comes up with an entire story in an instant. This is the quality that a writer needs, James says—the kind of imagination that “when you give it an inch takes an ell.” I love the idea that there is a full, complete, entire story behind every door, an ell of a story, as long as it’s a writer who is looking at those doors.

Q: Do you believe that you write the book you want to read?

I’m too close to what I’ve written to be able to answer that question entirely honestly, but I do know that that I try to write a book that, from a formal standpoint, I want to exist. This imaginary book…I can’t describe it; I can only try to write it. Rikki Ducornet writes in The Deep Zoo of a book that is “full immersive, polysensory, eloquent, in which everything is reactive, self-replicating; a mutable, complex, and functioning system with which the reader—who is now far more than the reader—may interact as she does with the real.” The dream of such a book is what attracts me to the Egyptian book of the dead, which isn’t a book at all; its spells and illustrations, in endless versions and variations, were etched on coffins. Some scholars call it the first guidebook, or even the first self-help book—it was intended to direct the dead through the landscape of the afterworld. I dream of using a book like that, a guide to the imaginary, detailed, pushing against the real.

Q: Do you think the media gives enough coverage to books?

Definitely not (although the situation might be different in the UK). I recently heard some magazine editors discussing on the radio how they had planned to decrease political coverage and increase arts and culture coverage after the election, but when Trump won, they decided to do the opposite. I think a lot of newspapers and magazines did this, because lately I see political coverage everywhere and very little books coverage—which seems like a shame. Books are different than politics, different than the Internet, different than television, and I imagine and hope that they always will be. I wish the media provided more images of people sitting alone with a book, not buying or doing anything else or even improving oneself, just reading.

Book Launch at Mac’s Backs-Books on Coventry

Q: Are there any books that you would describe as ‘life-changing’?

Books have determined the course of my life, the things I think and the way I understand my thoughts, they way I see life. They show me what to do and what to say. Some of the books that have done those things for me are: Ben Fountain’s Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk, U & I and The Mezzanine by Nicholson Baker, Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands/La Frontera, A Lover’s Discourse and Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes; Anna Karenina, Lolita, To the Lighthouse; Beloved, by Toni Morrison, One-Way Street, by Walter Benjamin, Hawthorne’s “The Custom-House,” Random Family, by Adrian Nicole LeBlanc, The Deep Zoo, by Rikki Ducornet, American Pastoral, by Philip Roth, The Portrait of a Lady, by Henry James, Writing Your Journal Article in 12 Weeks, by Wendy Laura Belcher…

Q: Are you a book shop person or a library person?

Library, perhaps in rebellion against my upbringing, which involved walking to the bookstore after dinner several nights a week.

Want to find out more about Lucy, her writing and work at the university?

You can read more here.

Or visit her website over here.

Find her on Facebook.

Or follow her on Twitter @poetrysecrets

Remember, if you enjoyed this post please share it. If there’s anything else you’d like to ask Lucy please leave a comment.

To have future posts delivered directly to your in-box, visit the sidebar on the right and subscribe to my blog, or to find out about new releases, competitions and freebies, subscribe to my newsletter and grab your free copy of my novel, I Stopped Time.