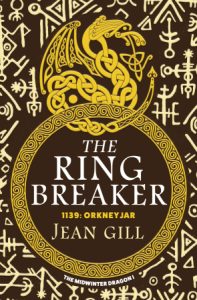

The Selfies Shortlist: Spotlight on The Ring Breaker by Jean Gill

An epic medieval saga of the last Vikings

Shortlisted for the Selfies Book Awards 2023 and the 2022 Chaucer Award.

In the twilight of the old gods, when the last Vikings rule the seas, two cursed orphans meet on an Orkney beach…

As thrilled as I am to be shortlisted for a third time for The Selfies Book Awards, I am all too aware how fierce the competition is.

Launched by BookBrunch in 2018 to recognise excellence in self-publishing, the awards are sponsored by Ingram’s award-winning self-publishing platform, IngramSpark® and are run in association with the London Book Fair and Nielsen BookData.

This time round, I find myself up against my writer friend, Jean Gill. I had the great pleasure of beta reading her shortlisted novel, The Ring Breaker. What’s more, both Jean and I used the same editor, Lorna Fergusson of Fictionfire.

There is a third historical novel in the shortlist, together with two psychological thrillers, a cosy murder mystery, a hard-boiled crime novel and a rom-com from the 2021 Selfies Book Awards winner, Halima Khatun. I don’t envy the judges!

Jean Gill is an award-winning Welsh writer and photographer who lives in the south of France with two scruffy dogs, a beehive named ‘Endeavour’, a Nikon D750 and a man. For many years, she taught English and was the first woman to be a secondary headteacher in Wales. She is mother or stepmother to five children so, understandably, life is hectic!

You may already be familiar with Jean’s award-winning series, The Troubadours Quartet, medieval adventures steeped in poetry, politics and passion. For The Ring Breaker, she returns to the 12th century, but with skalds instead of troubadours and Viking warriors instead of crusaders.

‘A skilfully written, beautifully researched coming-of-age story set in Viking Orkney.’

Lexie Conyngham, the Orkneyinga Murder series

The Ring Breaker, Book Description

Stripped of honour, facing bleak loneliness ahead, Skarfr and Hlif forge an unbreakable bond as they come of age in the savage Viking culture of blood debts and vengeance. To be accepted as adults, Skarfr must prove himself a warrior and Hlif must learn to use women’s weapons. Can they clear their names and choose their destiny? Or are they doomed by their fathers’ acts?

‘Reads from start to finish like a saga straight from a skald’s mouth.’

B A Morton, The Favour Bank

Chapter One, 1139

He was a sickly baby so his father took him to the beach and left him on the wrack-strewn pebbles for time and tide to claim a life not meant to be.

A kind man, his father had set out twice to do his duty, returning each time with the baby still in his arms. On the third occasion, his arms were empty. The mother flew through the door like a Valkyrie, her obedience tested beyond limits. As she later told the tale, she searched every cove and crevice for days, without food, drink or sleep, until she came across the cormorant.

It stuttered at her and opened its wings in warning, shielding its treasure on rocks velvety-green with moss. The treasure began to cry, the wail of a hungry baby, and the mother scrambled onto the rock, defied the bird’s anger, to snatch her baby from the nest and latch him onto her breast.

The cormorant stabbed her once with its beak, drawing blood from her cheek but she ignored it, feeling only the unexpected warmth of the baby in her arms. Warm, like the two other nestlings still huddling under the broody bird, which fixed her in a glassy-eyed stare, demanding what was owed.

What was due for the life of a baby? How could she free him from a debt to the otherworld?

His mother held him up to show the bird.

‘Skarfr,’ she named the baby. ‘Cormorant.’

The bird shook its wings, shaking sea-drops over them both in a salty baptism.

Without words, the cormorant told Skarfr’s mother that he would make sagas. She accepted this fate on his behalf along with a bone shard that the bird pushed towards her to seal their compact. Then she climbed down carefully, clutching him in her arms, watched by beady eyes as green as the moss. The cormorant stayed by its chicks and let her leave.

His mother, Kristin, bore the scar until the day she died. She said she deserved it. She told his father that the gods had returned their son to make sagas and had named him Skarfr but that he could follow whatever Christian naming rites he wished. And he could beat her for disobedience. But the baby was staying.

His father told her to hush. Whether he had no stomach for a fourth trudge to the beach or whether he accepted the gods’ intervention, he kept both the baby and the bone, saying nothing was ever so bad that something good couldn’t come of it.

The family lurched from one meagre meal to the next until Skarfr was seven years old. No further babies were born, or if they were, no cormorant intervened in their fate.

Desperate for plunder to trade for livestock, the father accompanied his lordship the Jarl on a raiding trip and was axed in the head as blood payment for some grievance against that same lord. The father’s name became a byword for loyalty. The longships returned and the father’s promise of riches was kept despite the inconvenience of his death. The Jarl paid generous compensation and the mother was now a wealthy widow. The family was allocated a longhouse, a cow, some sheep, chickens, and even a pony.

‘The price of a man’s murder,’ his mother said, as she inspected the cold hearth at the centre of cosy living quarters. Stone walls were caulked with peat and only one weakness in the patchwork roof allowed Orkney’s bitter wind to knife through, cutting smoke into choking backdraughts.

When the hearth was aglow and the fish smoking above it, the shades of a man, his wife and his son formed in the grey wisps and vanished into the sky. Or so it seemed.

‘Your father would have been happy here,’ she said, watching the smoke, her face so lined with poverty that grief left no trace.

She died of an ague within a year of his father’s death. Her last words were, ‘Always remember how your father was rewarded for his loyalty to the Jarl of Orkneyjar.’ Presumably she meant the longhouse. Skarfr was left rich and alone, too young to be either.

As was the custom, foster-parents were sought and their suitability debated at the Thing, their local council. Usually, an orphan would have many foster-homes, with perhaps a year in each to spread the burden, but in his case volunteers were torn between greed and fear. Skarfr’s wealth meant he would need one foster-father until he came of age but the rumours of how he got his name made good Christians cross themselves and many men fingered the hammer amulets beneath their jerkins.

‘Unnatural, touched by the gods,’ they whispered when they thought he couldn’t hear.

As always, the ruling jarl spoke for peace and found a solution that nobody could find fault with. Except Skarfr. And what did an eight-year-old know? A lot, as it turned out.

‘All the hallmarks of a Jean Gill novel – political intrigue, action and adventure, and a love story fraught with difficulties!’

Jane Davis, author of Small Eden

Join Jean’s special readers’ group at jeangill.com for private news and exclusive offers.

Read my interview with another of this year’s shortlisted authors, GD Harper, author of The Maids of Biddenden.

Read my interview with last year’s winner, Ivan Wainewright about his time travel novel, The Other

Times of Caroline Tangent.

***

To have future posts delivered directly to your in-box, visit the sidebar on the right and subscribe to my blog, or to find out about new releases, competitions and freebies, subscribe to my newsletter and I will send you a free copy of my novel, I Stopped Time, as a thank you.

While I have your attention, can I please draw your attention to my updated Privacy Policy. (You may have noticed, they’re all the rage.) I hope this will reassure you that I take your privacy seriously.

Remember, if you enjoyed this post please share it.

If you have subscribed to my blog but no longer wish to receive these posts, simply reply with the subject-line ‘UNSUBSCRIBE’ and I will delete you from my list.