The power of protest

A Q & A about political activism in fiction with Laura Katz Olson

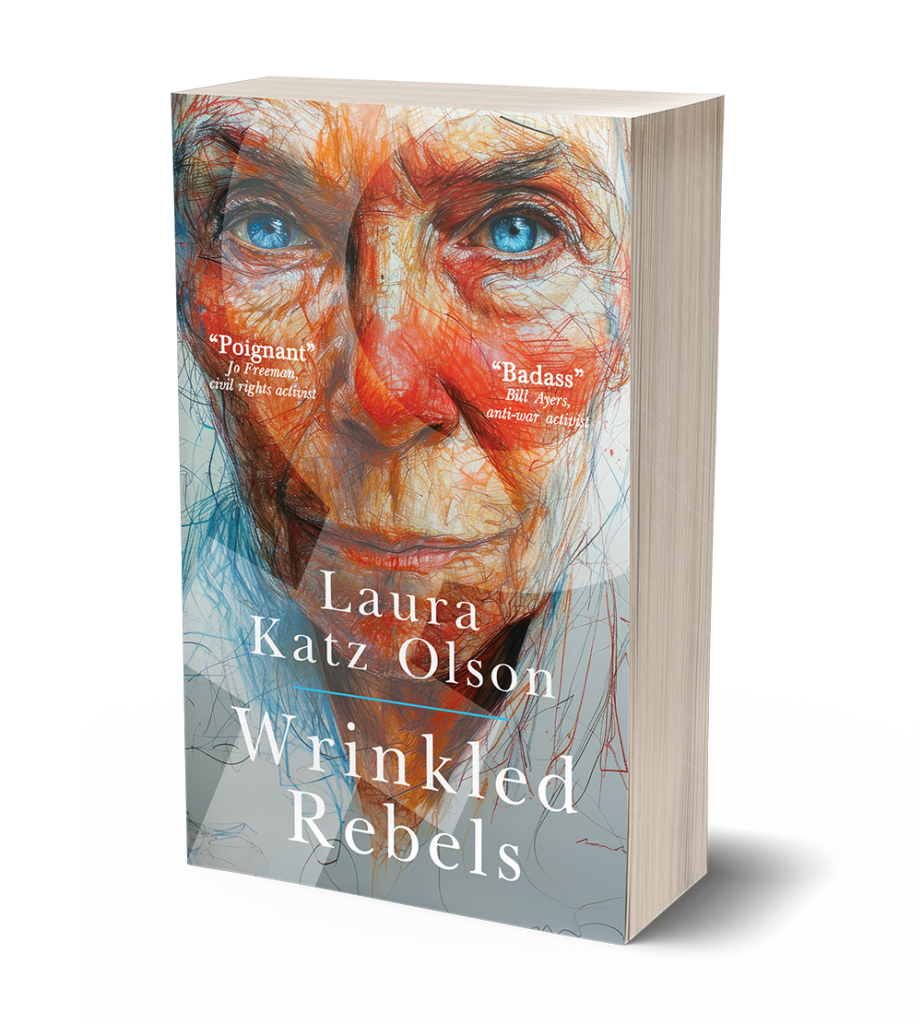

I see so few novels about political activism and protest that I was excited to learn about the upcoming release of Laura Katz Olson’s novel, Wrinkled Rebels (published by Vine Leaves Press, 23 July 2024).

Laura is Distinguished Professor of Political Science at Lehigh University. She received her bachelor’s degree from the City College of New York and her Ph.D. from the University of Colorado, Boulder. She has published widely in the field of aging, health care and women’s studies, her articles addressing social welfare policy, especially the problems of older women and long-term care.

Ethically Challenged: Private Equity Storms U.S. Health Care, published in March 2022, won a gold medal in The North American Book Awards, the Axiom Business Book Awards, and Independent Book Publishers Association (IBPA) Benjamin Franklin Awards and a silver medal in the Nautilus Book Awards. In addition, it won a National Indie Excellence Award, and was a finalist in both the American Book Fest Best Book Awards and Montaigne Medal/Eric Hoffer Awards. Laura also won the Joseph A. Dowling Award for Excellence in Research and Teaching at Lehigh University (2022). In 2009, she received the Charles A. McCoy Lifetime Achievement Award.

She enjoys running, bicycling, backpacking, kayaking, canoeing, cross-country skiing, playing the guitar and gardening. Her daughter, Alix Olson, is Assistant Professor of Women’s Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Emery University’s Oxford College. Prior to that she had toured internationally as a spoken word artist. She is the mother of Laura’s adored grandchildren, Zinn and Gray. Laura lives with her husband George DeRemer, a luthier and blue grass musician who plays the mandolin, fiddle, banjo, and guitar.

Wrinkled Rebels is her second novel. As the title suggests, it concerns a group of college friends who were brought together by common causes.

Having written about the subject in My Counterfeit Self, I reached out to ask if she would like to compare notes, and I’m pleased to say that she kindly agreed.

Jane: Welcome Laura, Can I begin by asking if you came to writing about the protest movement from personal experience and what it was that drew you to the subject?

Laura: I’ve been a staunch advocate of social and economic justice and participated in the anti-Vietnam war marches on Washington with college friends. I also had joined Core in its fight for civil rights (voting rights, anti-housing discrimination and the like), though I never joined in the dangerous organising efforts in the South. I remember how much I admired a particular classmate who quit City College (CCNY) in his junior year to devote himself to racial justice.

The seeds for these concerns were first planted in me at the High School of Music & Art, a place that offered not only music and art but also political awareness. College only intensified my interest in political activism, which was limited to nonviolent advocacy. My father was quite influential here—I promised him I would not engage in militant actions, and I abided by that; I think it also suited my cautious personality.

In the novel, I wanted to explore what it was like for people who were willing to jeopardise their college degrees and even professional careers, along with their health, well-being and possibly lives, for social and economic justice.

Laura: Your main character in My Counterfeit Self, Lucy, was in fact willing to sacrifice her career for the causes she believed in. What were your experiences with political activism?

Jane: I was a teenager in the 1980s and I have very clear memories of the Miners’ Strike and the Brixton Riots (I was fourteen, in hospital for dental surgery and was in a mixed ward, and every other person there had been injured during the riots). I happily sang along to Free Nelson Mandella and Biko at gigs but the closest I came to experiencing political activism was when my sister, along with other Amnesty International supporters, chained herself to the railings outside the British Embassy.

My own teenage years were dominated by two main pre-occupations, boys and music, and two main fears, Aids and the threat of nuclear war. Aids was the great unknown. The government issued every household with a leaflet about ‘The Tip of the Iceberg.’ At a time when teenagers wanted to experiment with sex, the message was that it could kill you. The threat of nuclear war was greater, and seemed imminent and urgent. Watching Reagan and Thatcher on the Nine O’Clock news (sacred in our house), there was genuine fear that there would be a newsflash and that the three-minute warning would sound. Music fed into this. Frankie Goes To Hollywood’s video for ‘Two Tribes’ captured the feel of the era, drumbeats representing panic. The boxing ring, the baying crowds, bets being placed: it was very cleverly done.

When choosing a cause for Lucy Forrester, my main character in My Counterfeit Self, I watched a documentary about Rod Stewart, which featured black and white footage of Stewart, then a folk singer with a guitar slung over his shoulder, taking part in the first of the protest marches from Trafalgar Square to Aldermaston. For me, that brought it all together. I had no trouble picturing Lucy at the centre of it all.

Jane: Do you think there was one defining moment of the 60’s protest movement, and if so, what was that?

Laura: There were a number of defining moments. One of them was the growing internal feuding of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), which eventually split the organisation into factions; a result was the escalating violent actions by the clique that became The Weathermen. Another defining moment was when the 60’s movement leaders publicly acknowledged the link between civil rights/anti-poverty issues and the Vietnam war, and various groups subsequently coalesced into a larger, more effective movement.

Laura: Do you think there was one defining moment that spurred Lucy to her activism?

Jane: When I made the decision to write about a poet, my initial aim was to explore what impact devastating childhood illness would have on a person. I discovered that many people in the public eye had suffered from polio – the late Donald Sutherland being just one. But when you breathe life into a character, and put them in a setting, you have to ask yourself what the character you’ve created would have done, and be true to that. Given that Lucy was already a poet and was a young woman in the late 1950s, the answer was that she would have been part of the protest movement.

Jane: Can I ask, what role does the women’s rights movement play in your novel?

Laura: My female characters, Deanna, Malaika and Rebecca, slowly become aware of the sexism they were subjected to only a few years after graduating from college and become feminists. Similarly, I became active in the women’s movement in the late 1970s. Baby boomer men, on the other hand, tended to face challenges in coming to terms with feminist ideas and concepts, especially in their personal lives. I wanted to explore these issues in the novel.

Laura: Lucy experiences multiple instances of gender discrimination as she slowly gains recognition as a poet. Did you have personal reasons for raising this issue in your novel?

Jane: I have to be honest, as a child, I never felt that there was anything that I couldn’t do because I was a girl. I progressed from climbing trees to climbing mountains, and because I wasn’t aware of a group that would take girls, I used to go with a local scout group. I left school at the age of 16, was a manager at 21, a director at 26 and a deputy managing director at 39. Our firm was thought of as being quite progressive in that out of a board of eight members, we had two female directors. As you say, there is a slow reckoning. Ask any woman, and she will tell you stories of harassment. They were so commonplace, we didn’t think to complain. As a woman in a boardroom, I could give you plenty of examples of when I proposed an idea which wasn’t taken up, only to have a male colleague propose the very same thing and have it voted in. There is that inbuilt sub-conscious discrimination. And I expect I would have had a very different story to tell had I tried to combine being a company director with motherhood. Because there were so few women in the financial services industry at senior management level, I didn’t see any examples of women who had succeeded in doing so. At the time, I prioritised my career, thinking that I knew my limitations, but perhaps that was received wisdom. I now work for a company where the managing director and the deputy managing director are both women, and the culture is very different to the macho culture of the 1980s.

Having said all that, my character Lucy is approximately my mother’s age, and lived at a time when women were expected to resign from their jobs when they became pregnant. The gender issues I reflect in the novel come from testimonials of poets like Carol Ann Duffy and the sexism they experienced at the hands of college professors. I think the situations I portray are representative.

Jane: To what extent do you think the protest movement was shaped by the disruption of the second world war?

Laura: At least one force was the segregation and racial discrimination against Black soldiers who fought for the U.S. and its ostensibly democratic ideals and came back to face overt discrimination in their own lives. Another force may have been the horrors of the atomic bomb and its effect on Japanese civilians as well as the fear of its use in a potential World War 111.

Laura: How did the disruption of the second world war affect your characters?

Jane: Born in a time of war, Lucy Forrester’s only early memories were of war. Talk of a third world war – the war to end all wars – permeated her adolescence. Bring a charismatic young woman like her governess Pamela into the equation, someone who was prepared to take a political stand, and of course Lucy was familiar with issues she might otherwise have remained ignorant of.

It’s 1958, supposedly a time of peace, but thoughts have once again turned to war. Imagine being eighteen years old, shipped to Christmas Island on National Service.

Your job? To stand on a white sandy beach and observe as scientists detonate nuclear bombs over the Central Pacific. No protective clothing is issued. When a signal is given, you must turn away and cover your eyes with your hands. After the flash goes off, you see your veins, your skin tissue, your bones, and through it all, diamond white, a second sun.

Around 22,000 servicemen performed similar roles. Some suffered radiation sickness immediately, and some of those died. For others, symptoms followed patterns seen in Hiroshima. They lost their appetites and ran high fevers. Their hair fell out in clumps. Others still appeared to be well for decades before developing cancers and other rare diseases.

Only over time were the dots joined up, convincing veterans that their illnesses and disabilities were caused by nuclear radiation.

Jane: Why was it important for you to write about older protagonists?

Laura: I’ve spent my career writing about aging politics and policies and even wrote a book several years ago about caring for my mother entitled Elder Care Journey. One thing I learned from my personal experience was that the reality of taking care of a frail older person is far more demanding than looking at the issues theoretically. And now that most of my friends and I have reached old age ourselves, I truly understand some of the challenges of aging. I wanted to explore issues of aging and caregiving through my characters and their different ways of dealing with them.

I also had a curiosity about what happened to the political activists of the 1960s/70s in terms of their lives throughout the decades and what they were like at 80 years old. I realised as I was exploring their lives, I didn’t want any of them to give up entirely on their idealistic ideals of their youth. They just had different ways of expressing them over the decades.

Laura: You, too, trace the lives of political activists into old age: Lucy, her husband Ralph, and her long-term friend and lover Dominic. What were your motivations in this regard?

Jane: It was only through researching the political issues for the book that I discovered the scandal of the British Nuclear Test Vets. Together with Hillsborough, The Post Office Scandal, OxyContin, and the NHS infected blood scandal, it will go down in history as one of the great cover-ups of our time. It is outrageous that Great Britain was alone in failing to compensate those who took part in nuclear tests. Largely ignored, dwindling in numbers, the Veterans referred to themselves as ‘ghosts’. When I began to write the book, the surviving Veterans and their families were still fighting for recognition. Every time they seemed to gain traction, the government changed and other priorities came to the fore. Even after the Prime Minister of Fiji stepped in and awarded each surviving veteran three thousand pounds, the British Government failed to act.

It seemed right to me that Lucy would go on fighting for a cause that she had believed in her whole life, and would use the platform she had gained in old age to highlight the plight of the British Nuclear Test Vets. It was only in 2022, some years after my novel was published, that the Vets were awarded medals recognising their contribution.

Jane: You show that your characters’ children and grandchildren are less politically engaged than previous generations. Do you think that is true generally or is it simply true of your characters?

Laura: Interesting question. Deanna has a daughter who is an activist and Rebecca and Keith have no children. One of the other three characters has children who are conservatives and the last two

have kids who are not engaged in politics. However, I didn’t mean my portrayal of these children as a general statement on the generations following the 1960s. In many cases, careerism may be more important to them than social and economic injustice. That said, I think that these later generations have

different causes and means of making them known. For example, today global warming and the destruction of the environment are vital concerns to young people. The U.S. Supreme court decision overturning Roe vs. Wade has stirred up pro-choice activism. Young people have rallied against police brutality against minorities. And, as seen by the recent campus uprisings, there may be strong,

latent energy to fight for other causes they believe in.

L: What are your views on the political engagement of recent generations?

Jane: When I think of youth movements, I think of Greta Thunberg, who proved that one person can make a difference. That is hugely influential to young people who feel helpless. But looking at the wider picture, degrees of engagement vary. In Scotland, politics is on the school curriculum so young people tend to be very clued up. In the UK, perhaps less so, but there have been many political protests in recent years, where people of all generations have taken to the streets to show support for Black Lives Matter, Ukraine and Palestine. Unfortunately, these only tend to hit the headlines where violence breaks out, or where traffic jams stop the great cogs of industry, such as the Just Stop Oil roadblocks, or where gatherings of

people are prevented, like the women’s Reclaim the Streets movement in the wake of Sarah Everard’s murder.

The other recent headline which effects everyone in arts and literature in in the UK is Baillee Gifford’s withdrawal of funding, after writers supporting Fossil Free Books boycotted events sponsored by the

investment firm. The intent was to persuade the firm to stop investing in fossil fuels backfired, when the firm advised that only two per cent of its investments were in fossil fuel, and that they were acting under instructions from clients. Now all attention has turned to the summer’s music festivals which are sponsored by Barclays. The flipside of the coin is that when the government takes action designed to combat climate change, such as the extension of London’s Ultra Low Emission Zone, there is also widespread protest.

Jane: One of the themes of your book is long-term friendship and its significance to your characters’ lives. Why did you want to explore that topic?

Laura: The bonds of lifelong friendship have always intrigued me. Certainly, I have made considerable effort over the years to maintain several of my college friends despite the geographic distance

and in some cases different values between us. And that was before zoom! As I age, these forever friends hold an increasingly important place in my life. My sister, on the other hand, had a different attitude. She used to describe herself as floating down a river on a barge and throwing off anybody who was no

longer compatible with her lifestyle and values at the time. She had thought that my “holding on” to people, as she put it, was irrational. In the novel I wanted to explore the meaning of lifelong friendships.

Laura: Your characters, too, maintain their connection throughout their lives, although Lucy and Dominic’s attachment is complicated, as is that between Ralph and Dominic. What were your objectives in exploring these relationships? Is the idea of forever friends meaningful in your own life?

Jane: My novel is about a character who was isolated through childhood illness. When she emerged from that, it was as a misfit. The first people to befriend her became the greatest friends of her life. In real life – as your book shows – friendships are hard to maintain. People move away for university or work, or in search of affordable family homes. Despite these obstacles, there are special friendships that survive the test of time, and those are generally with the people who know you through and through, because you have those core shared experiences. They were there when it all started.

Jane: Coming out as gay during the 1960s took great courage and often at the sacrifice of family, friends and career. What made you want to probe that issue through your character Rebecca?

Laura: My daughter, Alix, had been an activist for LGBTQ rights for ten years as a spoken word poet. I wanted one of my characters (Rebecca) to wrestle with what it was like to “come out” before the turn of the 21st century. I also wanted to portray a person who had similar concerns, hopes, dreams, disappointments and achievements as her heterosexual friends—that sexual orientation had little impact on one’s humanity.

Jane: Novels may be works of fiction, but they also exist in the real world and must represent life. In England and Wales, consensual sex between adult men wasn’t decriminalised until 1967, so yes, it would have been an enormous risk. One of the positive changes that I’ve seen during the timeline in which the book is set is social acceptance of same-sex partnerships, cemented by the legalisation of civil partnerships in 2014. No one should have to live a lie or hide who they are, as Ralph had to.

Jane: Can you name one book or movie that influenced you in writing this novel?

Laura: The 1983 movie, The Big Chill, had an influence on me, mostly because it was a favourite film of my close college friend Bill O’Connell, who has since died. The movie was a bittersweet reunion of all-white baby boomers in their thirties who were having an early mid-life crisis and who had betrayed their ideals. Wrinkled Rebels, although about baby boomers, includes diverse characters in old age and who haven’t betrayed their ideals. Nor are they disloyal to each other at the reunion. Also unlike The Big Chill it deals with important societal issues as well as the physical and emotional realities of old age.

Laura: Were there any books or movies that inspired you to write My Counterfeit Self, or any of your other novels?

Jane: I only ever embark on writing a novel with the seed of an idea. In the case of My Counterfeit Self, it was reader reviews that inspired me. Several commented that my prose read like poetry. I tried my hand at poetry, and I can tell you that it is a very different art – as I’m sure your daughter will attest! Having claimed that Lucy was Britain’s greatest living poet did not help. The poems I feature in the book are those she wrote during the long years of her illness – a child’s poems – but with the suggestion that these showed potential. But everything you watch or read during the writing of a book finds its way in somehow, so too does everything that happens to you. Two episodes of Alan Yentob’s arts program Imagine were particularly influential. The first was on Jim Marshall – he of the amp fame. He spent two years in a full body plaster. When he emerged, his father suggested that to build up his strength he learned to tap dance, and from tap dancing came an appreciation of rhythm which later translated to drumming, and from drumming came teaching musicians, and to cater for musicians came the invention of the amp. How incredible is that?

Praise for Wrinkled Rebels

“It’s a joy to finally read a sweeping historical novel that tells the real story of the lives of those of us lucky enough to have come of age into the New Left and the mass movements of the Sixties. Contrary to the Forrest Gump zombie conventional wisdom narrative of the era as a giant train wreck, nothing stopped there: the organising work continued throughout our lives, based in the solid values of justice and peace and equality manifest over 60 years ago. Meticulously researched and lovingly written, Laura Olson has succeeded in capturing the true history of our rebellious cohort as well as our living spirit. What a blessing she has given her readers by reminding us that it ain’t over.”

—Mark Rudd, political organizer, anti-war activist, lecturer, and author of Underground: My Life with SDS and the Weatherman

“Wrinkled Rebels takes us back to the youthful struggles for social justice and the anti-war demonstrations that characterized the 1960s and 1970s. What happened to those political activists? In this poignant narrative of three men and three women, now eighty years old, Olson deftly captures not only their ongoing commitment, struggles and setbacks as they reach retirement and old age but the power of abiding friendship to heal each other’s tired spirits.”

—Jo Freeman, civil rights activist, a founding member of the feminist movement, lawyer, and among other books, author of Women: a Feminist Perspective, The Politics of Women’s Liberation, Waves of Protest: Social Movements since the Sixties.

“’Wrinkled Rebels’ is a fine novel about young activists of the 1960s moving from adolescence to middle age and beyond. Laura Katz Olson has managed to capture many of the personal nuances and life complications confronting those who sought so urgently to save the world. Younger readers in particular will grapple with the lives of their grandparents’ generation and old-timers will likely rehearse their own life experiences.”

—Paul Buhle, founding editor of the SDS journal Radical America; retired Senior Lecturer, Brown University

“For those who want to learn about the momentous years of social struggle in the 1960s – the civil rights movement; the anti-Vietnam war movement; the women’s liberation movement – Olson gives an engaging and lively flavor of these events through six different relatable characters. Not only does the reader see their participation in these movements, but also the bonds and camaraderie that come from fighting for social change together.”

—Nancy Rosenstock, author of Inside the Second Wave of Feminism: Boston Female Liberation 1968-1972, An Account by Participants

Social Media and Buy Links

Website: https://www.wrinkledrebels-olson.com

Facebook: bit.ly/4e5cS2b

Instagram: bit.ly/45h6vVy (@sallyboo123)

LinkedIn: bit.ly/3x0LIc6

Twitter: bit.ly/3XrvQu7 (@lauralee111)

Wrinkled Rebels can be purchased at:

Amazon: amzn.to/3RcuJKA

Vine Leaves Press: https://vineleavespress.myshopify.com/products/wrinkled-rebels-by-laura-katz-olson

To have future posts delivered directly to your in-box, visit the sidebar on the right and subscribe to my blog, or to find out about new releases, competitions and freebies, subscribe to my newsletter and I will send you a free copy of my novel, I Stopped Time, as a thank you.

While I have your attention, can I please draw your attention to my updated Privacy Policy. (You may have noticed, they’re all the rage.) I hope this will reassure you that I take your privacy seriously.

Remember, if you enjoyed this post please share it.

If you have subscribed to my blog but no longer wish to receive these posts, simply reply with the subject-line ‘UNSUBSCRIBE’ and I will delete you from my list.