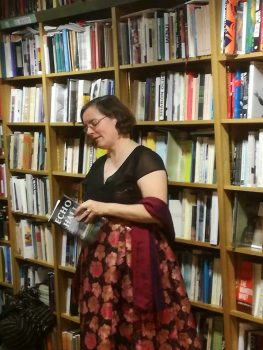

Today, I’m delighted to welcome Virginia Moffatt to Virtual Book Club, my interview series which gives authors the opportunity to pitch their novels to your book club.

Virginia was born in London, one of eight children, several of whom are writers. Her eldest brother writes about theology and politics, one sister is a poet, a second a translator and her twin sister is a successful author.

Virginia has always been a writer but began to take it seriously only in 2004, when she first had the idea for Echo Hall. In 2009, she set up her blog, ‘A Room of My Own’, where she publishes flash fiction, short essays and reflections about writing and reading.

Virginia also writes on political and faith issues. She has recently edited a collection of essays, Reclaiming the Common Good: How Christians can help rebuild a broken world, published by Darton, Longman and Todd in 2017. She has also written a Lent course, Nothing More and Nothing Less, based around the film I, Daniel Blake,also published by Darton, Longman and Todd.

After working in social care for 30 years, Virginia left local government to work for the Christian think–tank Ekklesia in 2014. She currently works for a multi-academy trust as a procurement and contracts manager.

Virginia is married to Chris Cole, director of Drone Wars UK. They have three children and they live in Oxford.

Echo Hall has been longlisted for the Bridport First Novel Prize 2015 and Retreat West Opening Chapter Competition December 2015, but what makes it particularly suitable for book clubs?

It tells the story of three generations of women who experience love, loss and conflict during times of war. When Ruth marries Adam Flint in 1990, she moves to Echo Hall and discovers a house full of secrets. As she begins to explore the conflicts of the past and is taken back to the stories of her predecessors Elsie and Rachel. In doing so she is able to help the Flint family heal and discover what it is she really needs and wants.

I am fairly sure Echo Hall will appeal to book club members as I’m in one myself – The Cowley Consonants. In my experience, we all respond best to a book with a good story, great characters and which makes us think. I believe Echo Hall meets all three of these criteria and my belief is also confirmed by the fact that my book club loved it. Some of them were even willing to say so on my book trailer!

In the early nineties, newlywed Ruth Flint arrives at Echo Hall to find an unhappy house full of mysteries that its occupants won’t discuss. When her husband, Adam, is called up to the Gulf War, her shaky marriage is tested to the core.

During World War 2 Elsie Flint is living at Echo Hall with her unsympathetic in-laws. While her husband Jack is away with the RAF, his cousin Daniel is her only support. But Daniel is hiding a secret that will threaten their friendship forever.

At the end of the Edwardian era, Rachel and Leah Walters meet Jacob Flint, an encounter leading to conflict that will haunt the family throughout World War 1 and beyond.

As Ruth discovers the secrets of Echo Hall, will she be able to bring peace to the Flint family, and in doing so, discover what she really wants and needs?

“Virginia Moffatt tells a Gothic tale with a modern twist. Her saga of a troubled family explores cycles of violence that can tear lovers apart, but also whole communities, and whole continents.”

Twenty words on why your book should be a reader’s next read…

It has ghosts, family secrets, three strong women and questions about the nature of war. How can you resist?

Where is the book set and how did you decide on its setting?

The book is set on the borders of Wales, in a fictional village called Whetstone. The Flint family own a quarry over the border in another fictional village, Bryngraean. There’s also a local market town, Sandstown.

The book was always going to be set there, because I have loved Wales ever since I was a child. The hills and mountains are dramatic, the weather is often wet and wild, and you get a lot of fog, which is enormously helpful when building atmosphere. I deliberately made the area fictional so I wouldn’t trip up and make mistakes, but it is drawn from a wide range of real places. Whetstone is an amalgamation of many Welsh villages I’ve passed through. The tiny post office is drawn from an actual one that used to exist in the village of Pont-Rhyd-Y-Groes,Ceredigion (where my friend Ann lived). The quarry is based on the entrance to one near Llangollen, and the Llechwedd Slate Caverns in Snowdonia. Sandstown is based on a mixture of Cathedral towns, including Hereford, Shrewsbury and Chester. Arthur’s Stone, a key location in the novel, is my reimagining of a landmark by that name near Bredwardine, Herefordshire. While the interior of Echo Hall draws a lot from a visit to a country house called Scolton Manor, which is in Pembrokeshire.

I have written more about my fictional landscape here.

Did you know where this book was going to go right from the start?

Pretty much. I first had the idea for it in 2004, when we were living in a small hamlet. I’m a scaredy cat and living in an old, creaky building I used to imagine I could hear voices at night time. Such imaginings led me to wonder what if those voices were real. Whose would they be, what would they be saying and why? I worked out the answer to that question pretty quickly, mapped out the first two generations (Ruth and Elsie) and how the story was going to end. I had to flesh out a lot of the detail after that, Rachel’s story emerged later and I added a prologue and epilogue with Phoebe (Ruth’s daughter) fairly late in the day, but otherwise the basic plot of the novel is pretty much as I envisaged it at the outset.

Do you believe that you write the book you want to read?

Yes, of course. If I bore myself, I bore my readers, so I have to care passionately about what my characters do and why. Because I was writing Echo Hall at the same time as raising a family, working and studying, I had to live with it for a long time. Over the many years I took to write the novel, I often discovered things about my characters that I hadn’t expected to which helped me flesh out the story more. I’ve read the manuscript thousands of times, but I’ve still been able to make myself laugh and cry at various points, so I hope the readers will too.

A good ending should fix the shape and meaning of the whole novel. How did you make sure yours did exactly that?

Up until 2015, I was totally satisfied that this was the right ending for the novel, but I kept thinking about Phoebe, Ruth’s daughter. She didn’t have a tale to tell herself, but I realised she would bring the novel up to date, and by having a section set in 2014, I could make a direct link to the anniversary of the beginning of World War 1. So I created a prologue and an epilogue which don’t change the overarching story but I hope help frame its themes more clearly.

Do you ever actively think about creating layers in a novel so that the reader can get more out of a second or third reading?

Definitely. I love books that do this. One of my favourite authors, David Mitchell is very clever at it, so I’ve paid a lot of attention to his work. Echo Hall is a novel about the echoes of history, so I very intentionally spent a lot of time creating echoes in different ways in the text. The most obvious ones are the repeated situations that happen in each generation: births, miscarriages, marriages, deaths. But I added others. There are annual events, Christmas, Easter,Mayday, Harvest; there are phrases and paragraphs to describe the seasons that recur time and again, and the characters meet at the same locations, Arthur’s Stone, the Quaker Meeting House, the King Edward hotel. Additionally, I used some key colours, red-gold, orange-black and ash-white. A couple of readers have felt some of this was a bit repetitive, but I think most appreciated the effect I was trying to achieve, and I hope that during re-readings they’ll discover more.

How important is historical accuracy when writing fiction and how faithfully does your novel stick to the written record?

I think accuracy is tremendously important. We all have our interpretations of what the events of history mean, but we have to get our facts right in order to make our argument successfully. Additionally, while most people probably won’t notice, it will probably jar the narrative for those who know their history. So I think I owe it to readers to get it right the first time.

I spent a long time checking things out, but still found I made mistakes. There is one scene in the book where I originally had characters discussing Guernica. It was only at the proof reading stage that I double checked the dates and realised the conversation was happening two years before the event. I found it hard to think of the 1990’s section as history as I lived through them, but I found here I had to check even more than the World War 1 and World War 2 sections. My memories of when key events happened often proved to be faulty.

I also discovered the British Meteorlogical Society has a website that provides weather reports going back a century, so I found it nerdishly satisfying to check the weather in the novel matched the weather in that area at the time. (Though it did, rather annoyingly, mean I had to cut some snowy scenes at one point).

How do you make sure you long hours of research don’t show up on the page?

It’s really tricky isn’t it? You spend ages researching stuff that is fascinating and then there is no room for it. When I started Echo Hall I was meticulous about my research. I read some fascinating books about women in Edwardian times which alongside Roy Hattersley’s The Edwardians was enormously helpful, as was Adam Hochschild’s To End All Wars. For World War 2, I particularly appreciated Juliet Gardiner’s War Time Britain: 1939-1945 for period detail, while Nicolson Baker’s Human Smoke is an unforgettable collection of writings from the key players of the period which make you revisit everything you know about that War. I also was delighted to find a recording of BBC news broadcasts from the early 1940’s which proved invaluable. And like many writers I frequently googled dates of details of events to make sure I got things right.

I made copious notes on these but very little made it into the book as most of it would bog down the story. Wherever possible, I tried to use detail that would enhance the narrative or help pass comment. For example, I refer to the fact that after World War 1, women used to stand weeping on the streets on Remembrance day, something I’d picked up from Adam Hochschild’s book. I quote directly from a BBC news report in 1942 as it has a direct impact on Elsie. And I use a real life TV broadcast I watched in 1991 when the bombs started falling on Baghdad as it links Ruth to a memory of the previous August.

Do you think political statements belong in literature? Would you write a novel that was a political tract?

Most of my favourite authors, Dickens, the Brontes, Forster, Atwood, Walker, Robinson, Adichie, Mitchell, Winterson are political in some way, so yes, I think literature and politics can go hand in hand and it’s important that they do. However, writing a novel as a political statement is the worst way to go about it as it kills the story before you’ve even started. I love EM Forster, but I always feel his novel Maurice suffers from this. Forster wanted to write about being gay in a sympathetic way at a time when it was frowned on. I really admire the sentiment but I found the book plodding and dull, because I felt he came up with the politics first and the narrative second. It’s always better to do it the other way. I care about the state of Victorian boarding schools because I’m horrified at what happens to Nicholas and Smike in Nicholas Nickleby, and Jane in Jane Eyre. Celie’s plight in The Color Purple makes me question the interconnections between racism, sexism and poverty, while the situation of the unknown narrator of The Handmaid’sTale, gets me thinking about why so many societies subjugate women. When I started writing Echo Hall, I began with a ghost story. It was only as the narrative began to emerge that I realised I could use the book to discuss the nature of war and peace. So I hope the politics don’t overshadow the novel, but are done subtly enough to make readers think about the issues I’m raising.

How do you get into the mind-sets of a people living in the different decades in which Echo Hall is set?

I think this was relatively easy for me as I had a direct connection to all three time periods. As noted above I lived through the 1990’s and the Gulf War had as much of an impact on me as it does on Ruth. My parents lived through World War 2, my father and an Uncle were in the Navy, another Uncle in the Army and a third in the RAF (like my fictional Jack). One of my grandmothers had to live with all three of her sons going to war, and two of my aunts had husbands who were away. In the previous generation, my grandfather was a prisoner of war, and two great uncles died. So I grew up with a real understanding of what those wars were like to live through and what they did to people.

I also love 1940’s films, so that helped in capturing the speech patterns of that era. There’s even a nod to one of my favourites, A Matter of Life and Death. And I also re-read Orwell’s Keep the Aspidistra Flying and several Greene novels. For the Edwardian era, I went back to Forster’s Howard’s End, and a wonderful collection of letters between two real Edwardian women Ruth Slate and Eve Slawson Dear Girl: The Diaries and Letters of Two Working Women edited by Tierl Thompson. Both were very useful when I rewrote Rachel’s story in the form of letters, though I fear at times I lapsed a bit into Jane Austen’s language!

Do you have a technique for keeping track of your fictional canvas and timeline?

Yes. I have a huge pile of notebooks that I used to create Echo Hall. The book has five sections covering the three different periods. I not only had to keep track of the narrative, but I had to make sure that it followed the historical timeline accurately. I was constantly writing out lists of the fictional and real events that were happening in a particular year, and making sure the text had that accurately. Even so, I still made mistakes (such as the one I highlighted above) though I hope we picked them all up in the editing process!

Neil Gaiman said, ‘Start telling the stories that only you can tell, because there’ll always be better writers than you and there’ll always be smarter writers than you. There will always be people who are much better at doing this or doing that — but you are the only you.’ Why was this a story only you could tell?

Firstly, only I have my own artistic sensibilities. I love Gothic novels, family sagas, historical fiction and stories that have something to say about the world we live in. All of which I’ve brought to Echo Hall. Secondly, it took me over thirteen years to get this book to publication, during which time I spent hours thinking and writing about my characters – no-one else but me could have brought them to life after that. Finally, the novel follows different experiences of war. There are those who fight, those who choose not to, and women who are left behind. As the daughter, granddaughter and niece of men who went to war, and women who stayed at home, and as a pacifist married to a long term peace campaigner, I believe I have a unique insight into why people make those choices and what they mean.

Want to find out more about Virginia and her writing?

Virginia’s personal blog is https://virginiamoffattwriter.wordpress.com/

Her Unbound page is https://unbound.com/books/echo-hall/

Follow her on Twitter @aroomofmyown1

Remember, if you enjoyed this post please share it. If there’s anything else you’d like to ask Virginia please leave a comment.

To have future posts delivered directly to your in-box, visit the sidebar on the right and subscribe to my blog, or to find out about new releases, competitions and freebies, subscribe to my newsletter and grab your free copy of my novel, I Stopped Time.