In England’s green and pleasant land

Why I decided my leading man should be an opium grower

The discovery that Mitcham – only three miles from where I live – was once the opium-growing capital of the UK made me decide that Small Eden’s leading man, Robert Cooke, should be a physic (or physick) gardener. The term has fallen out of use, but it means a grower of medicinal or healing plants.

At the beginning of the novel, Robert Cooke’s physic garden is prospering. He has been found himself in the right place at the right time, growing a crop that is very much in demand. The name Mitcham is a guarantee of quality. There is no county on which druggists and wholesalers rely more for their supplies. He has also benefitted from technology, has his own copper stills, and is looking for more land so that he can expand his business.

Poppy, papaver somniferum

“Then comes the Poppy; two or three acres of these were grown. They were sown in early Spring broadcast and thinned out to about six inches apart; they grew about 5 or 6 feet high, bearing large heads as large as your fist – their stalks were thick and strong, standing on the ground until they were quite dry, then they were gathered and stored for sale.”

James Malcolm A Compendium of Modern Husbandry, principally written during a survey of Surrey III (1805)

Poppy was only one of a number of medicinal plants grown in the area. Peppermint was the primary crop, used to treat cholera gripes and pains in the stomach. Then came camomile. Schools closed for July and August, but this was no holiday. It was so that children could help gather the flowers. Rose-water was used to treat weak eyes, as well as for cosmetic purposes. Belladona was used for plasters for bad backs. Henbane was grown for the treatment of toothache, asthma, and nervous diseases, but was also known to be highly poisonous. Marsh Malop was grown for its root, which was used for poultices for bad legs and bruises. The liquor produced by boiling horehound and liquorice together was used to treat colds, coughs, asthma, and bronchitis. And so on. The legacy that has remained in the area is lavender growing. Carshalton still has two lavender farms. The larger of the two Mayfield Lavender draws huge visitor numbers in the summer.

The Victorian pharmacy – kill or cure

The Victorians understood that the same plants that could heal when taken in small doses could kill when taken in large quantities. But pharmacists were not yet regulated, and there was no requirement for ingredients – or more importantly, quantities of ingredients – to be listed on the labels of pre-mixed products. Visit any Victorian pharmacy and behind its gleaming counter you would have found Sydenham’s Laudanum for dysentery and camphorated tincture of opium for asthma. Used for the relief of headaches, migraines, sciatica, as a cough suppressant, to treat pneumonia, and for the relief of abdominal and bowel complaints and women’s cramps, opium was an essential in any medicine cabinet. Far from having a seedy reputation, it was respectable. The royal apothecary ensured Queen Victoria’s household was well-stocked, and Prime Minister William Gladstone is said to have drunk opium tea before making important speeches.

‘No household should be without a supply‘

Opium wasn’t the only potentially dangerous medicine that Victorians were exposed to. Arsenic was used in medications to treat everything from asthma and cancer to reduced libido and skin problems. It came under regulation from the 1851 Sale of Arsenic Act but its aim wasn’t to stop your friendly pharmacist (or grocer) selling it to you. It simply required vendors to keep records of purchasers and the reason for their purchases. In Small Eden I have Miss Hoddy mention to Robert that arsenic compounds, particularly the green pigment, were used in the manufacture of wallpapers. There was growing evidence that arsenic was toxic, but as with tobacco, there was a lot of denial.

(Aside: update added 30 April 2022 – publication day. Arsenic was also used in the manufacture of book covers. This piece in National Geographic tells how Melissa Tedone has launched ‘Poison Book Project’ in an attempt to track them down!)

Mrs Beeton was the go-to household authority of the Victorian era. If Mrs Beeton told her readers that it was safe to dose their children with this or that, then people took her word for it. If she told people to doctor sour milk with Boracic acid – a substance that even in small amounts can cause nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain and diarrhoea – then they doctored their milk.

Mrs Beeton’s famous Book of Household Management recommended that no household should be without a supply of powdered opium and laudanum, and she included a recipe for laudanum. But Mrs Beeton was aware of the dangers the drug posed. She warned that opium-based preparations should not be given to children, writing:

‘The following preparations, which are constantly given to children by their nurses and mothers, for the purpose of making them sleep, often prove fatal:-Syrup of Poppies, and Godfrey’s Cordial. The author would most earnestly urge all people caring for their children’s lives, never to allow any of these preparations to be given, unless ordered by a surgeon.’

Unfortunately, for the working classes, dosing their infants so that they would sleep through much of the day was a necessity. Working class women had to work.

“The plot here of one man’s dreams to memorialize his two dead sons by building his “pleasure gardens” for them, is enhanced by watching this family saga unfold. Finally, I thought it fitting that Robert’s main employ was growing poppies for the opium trade, and we all know how that drug can be both healing and destructive. That’s quite a metaphor, if you ask me.”

The Chocolate Lady’s Book Review Blog

Excerpt from Small Eden

For several blessed days Robert thought that he and his mother had arrived at a new understanding, that he no longer had to be the small boy, worried that whatever he wanted would in some way cause her heartache. Now, suddenly, she’s meddling in every aspect of his life. Diversify indeed! But it was Freya who first showed him Dr Bull’s Hints to Mothers, a pamphlet highlighting the dangers of opiates in the nursery. One of the women at church had given it to her, perhaps ignorant of the nature of his business, but more likely not. Of course he doesn’t agree with the practice of dosing up babies so that they sleep all day, he told his wife, but yes, he’s aware it goes on. Working mothers have little choice but to leave children for hours at a time, so they doctor their gripe-water. And it’s not just the poor. Mothers read the labels that say Infant Preservative and Soothing Syrup. They think that ‘purely herbal’ and ‘natural ingredients’ means that products are safe. Though it was chilling to read about case after case of infant deaths linked to over-use.

As many as a third of infant deaths in industrial cities.

And he, who has buried two sons.

But even Dr Bull didn’t condemn the use of opiates outright. They are medicines, he wrote, and like any medicine, ought to be prepared by pharmacists. The trouble is, Robert told Freya, that until recently any Tom, Dick or Harry could operate a pharmacy. And hasn’t he been vocal in his support for an overhaul of the system?

As for adults, they’re capable of making their own decisions. Freya wasn’t suggesting that she shouldn’t take her ‘women’s friends’ when she needed them, was she?

Why did it take so long for Britain to ban opium?

The Victorian attitude to opium was complex. In the 19th Century, Britain fought two wars to crush Chinese efforts to restrict its importation. Why? Because opium was vital to the British economy. Chinese luxury goods such as porcelain, silk and tea were in great demand at home but, since there was no demand in China for European goods, it became necessary to create one (or pay for goods in silver and gold). Britain’s solution was to export opium grown in India (then governed by Britain). In India, opium was the regime’s second highest source of revenue, second only to land tax. Britain was not alone in this. Other European countries also went into the business of importing opium and in the process created a nation of addicts, which ensured continuing demand. And so Indian peasant farmers needed to be encouraged to go into the business of growing opium poppies.

The anti-opium movement

In 1874, a group of Quaker businessmen formed The Society for the Suppression of the Opium Trade. Then in 1888 Benjamin Broomhall formed the Christian Union for the Severance of the British Empire with the Opium Traffic. Together, their efforts ensured that the British public were aware of the dangers that opium presented – and of the damage it was causing.

Excerpt from Small Eden

“Indulge me if you will while I explain how the Indian trade operates – a system that the House of Commons condemned this April last. The East India Company – with whom I’m sure you are familiar – created the Opium Agency. Two thousand five hundred clerks working from one hundred offices administer the trade. The Agency offers farmers interest-free advances, in return for which they must deliver strict quotas. What’s so wrong with that? you may ask. What is wrong, my friends, is that the very same Agency sets the price farmers are paid for raw opium, and it isn’t enough to cover the cost of rent, manure and irrigation, let alone any labour the farmer needs to hire. And Indian producers don’t have the option of selling to higher bidders. Fail to deliver their allocated quota and they face the destruction of their crops, prosecution and imprisonment. What we have is two thousand five hundred quill-pushers forcing millions of peasants into growing a crop they would be better off without. And this, this, is the Indian Government’s second largest source of revenue. Only land tax brings in more.”

More muttering, louder. The shaking of heads and jowls.

“I propose a motion. That in the opinion of this meeting, traffic in opium is a bountiful source of degradation and a hindrance to the spread of the gospel.” Quakers are not the types to be whipped up into a frenzy of moral indignation, but their agreement is enthusiastic. “Furthermore, I contend that the Indian Government should cease to derive income from its production and sale.”

Robert looks about. Surely he can’t be the only one to wonder what is to replace the income the colonial government derives from opium? Ignoring this – and from a purely selfish perspective, provided discussion is limited to Indian production – his business will be unaffected. Seeing his neighbours raise their hands to vote, Robert lifts his own to half-mast. Beside him, Smithers does likewise.

Then there was the thorny issue of class. The upper and middle classes viewed the heavy use of opiates among the lower classes (who used it as a pick-me-up before going to work) as ‘misuse’ of the drug. At the same time, however, they saw their own consumption as necessary, and certainly no more than a ‘habit’. And habit wasn’t yet recognised as addiction. That would come later.

The 1868 Pharmacy Act, which aimed to regulate the sale and supply of opium-based products, was popular among chemists. Legislation which stipulated that opiates could only be sold by registered pharmacists secured their role as gatekeepers. However there was still no limit on the amount that could be sold to individuals. The real change came with a shift in public opinion.

The beginning of the end

The time comes when Robert Cooke must make a choice. He can either diversify (as his mother suggested when the anti-opium movement started making their voices known). Or he can gamble that the government will ban cheap foreign imports and that the price of domestic produce will rise. Robert Cooke is a risk-taker. He decides to gamble.

After much lobbying, the British anti-opium movement won a significant victory. In 1910 it secured the government’s agreement to dismantle the India-China trade. That is where my novel ends. But the battle didn’t stop there. Following the International Opium Convention in 1912, countries committed to stop trading in opium, morphine and cocaine. However, at the outbreak of the first world war, use of opium and cocaine was still legal. Military men were found to be addicted to drugs, leading to concern that it was corrupting their character. Emergency legislation was rushed through parliament, and those measures were finally made permanent in the Dangerous Drugs Act 1920. It was only then that use of opium and its derivatives was limited to strictly medical use.

***

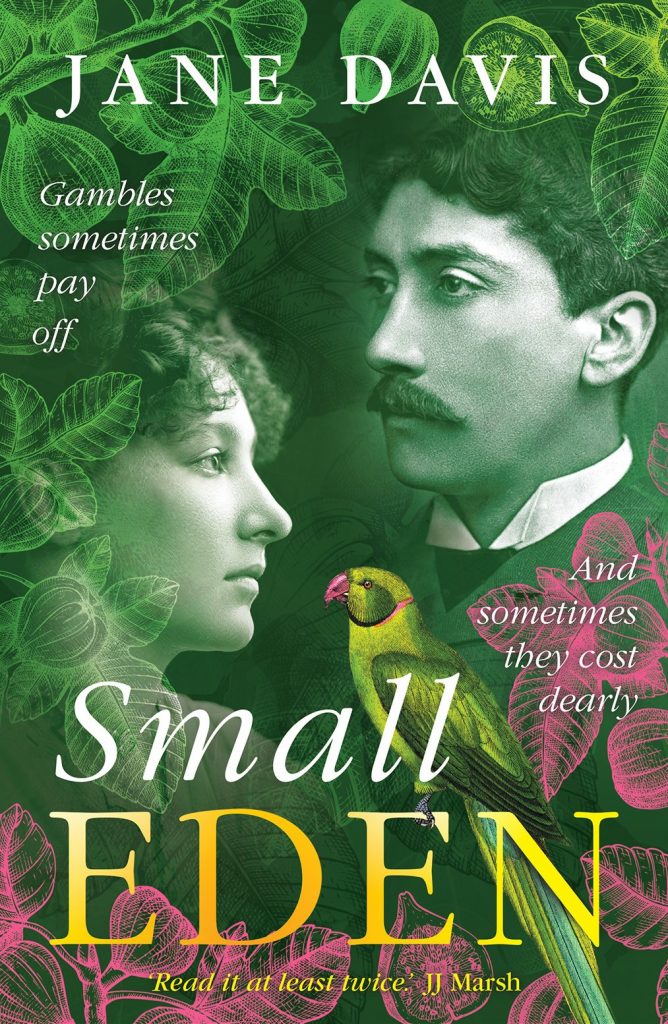

Small Eden will be out on 30 April 2022. Pre-order from 5 April 2022 to have it delivered to you on the date of release.

To have future posts delivered directly to your in-box, visit the sidebar on the right and subscribe to my blog, or to find out about new releases, competitions and freebies, subscribe to my newsletter and I will send you a free copy of my novel, I Stopped Time, as a thank you.

While I have your attention, can I please draw your attention to my updated Privacy Policy. (You may have noticed, they’re all the rage.) I hope this will reassure you that I take your privacy seriously.

Remember, if you enjoyed this post please share it.

If you have subscribed to my blog but no longer wish to receive these posts, simply reply with the subject-line ‘UNSUBSCRIBE’ and I will delete you from my list.