Today, I’m delighted to welcome Colleen Mills to Virtual Book Club, a series in which I put questions to authors about their latest releases. If there’s anything else you’d like to know, you’ll have the opportunity to post your questions at the end.

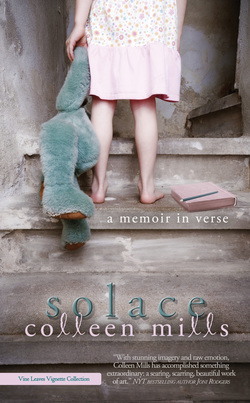

Earlier this year, I was extremely privileged to receive an advance copy of Colleen’s first published work, Solace: A Memoir in Verse, released by Vine Leaves Press in June of 2015). In it, she recounts the memories of seven siblings who are domestic violence survivors and explores the interaction of memory, trauma, and identity. Solace is one of those rare pieces: beautiful, authentic, raw, shocking, but without a hint of self-pity. I was mesmerised.

Colleen Mills is a teacher, writer, and editor living in the Hudson Valley Region of New York. She holds an MFA in writing from Goddard College and a BA in Secondary English Education from SUNY New Paltz.

Q: Colleen, this is a deeply personal piece. It must have taken a great leap of faith to let anyone else read it, let alone allow it to find a wider audience – although I’m so glad you did. Tell us, how did it came about?

In some ways I think I’ve always been writing Solace, even before I knew that I was. As a child, but especially in high school, I wrote pieces that dealt with domestic violence or more abstract family unhappiness and handed them in for assignments. I told myself that, if anyone asked, it was just creative writing. I could hide behind that. No one ever asked.

I think there is more openness and awareness about domestic violence now (which is not to say that stereotypes and silence have diminished). In the eighties I don’t think people who suspected felt they could ask or interfere. My own grandparents who lived next door never said anything although they certainly knew some unavoidably obvious details.

Living felt like imprisonment in my own body. To me, truth was a concept people pretended to live in public because that was my experience of it at home. No decision was pure to my needs. Nothing was truly mine, except to some degree writing. It makes me incredibly sad to say that about my life and even more sad to know that there are so many others living that truth. As a teacher I see so many kids who have these little hints of sadness, but actually the threshold for intervention is very high. Near the start of my teaching career, I was also involved in a custody battle with my parents for my two younger siblings. I heard my siblings testify in open court to a jury of strangers about the conditions of our lives. It was embarrassing and humiliating and, although we had clearly chosen to have our voices heard, I think it really came to the surface that in addition to all the wrongs done to us, we had to suffer also from the weight of ownership of a wrong we had no control of and no responsibility for.

The dedication of the book reads, “For the seven and for the many.” I suppose in reading it, it’s still just words on the page, but I felt that I had lived my life or been brought into existence to come to that moment in court where I could help my younger siblings, and in publishing this book I hope that some of the many also find some solace, just as I found to some small degree when I read authors who brought words to the experiences I couldn’t speak openly about.

Q: You’ve mentioned the word, ‘solace’. At what point in writing the memoir did you come up with its title?

Solace was originally title A Gallery of Echoes. That phrase shows up in the book, and in earlier versions I felt that was representative of not only the content but of the vignette style. It is a bit like a gallery walk through seven lives. As I revised and fleshed out the more abstract commentaries of the work, the experience became the vehicle, but the purpose of the writing became more important to me as I asked myself, “Why write this? Why publish this?” Solace is its title and its purpose.

Q: You could have told your story in any number of ways. Why did you chose verse?

Maybe artists have a special calling toward an art form. As a kid, I wrote in diaries, I wrote stories, I drew, but as early as third grade I remember being drawn to the special beauty of painting with words in poetry. In third grade we made little nature haikus and wrote each on the accordion folded squares of a long strip of paper. Those were glued to cardstock that had been wrapped in nature coloured wrapping paper and tied up with satin ribbons. We were supposed to give them as gifts to our parents or someone, but I kept mine in my little shoebox treasure trove for years. Poems are a gift to someone. Each seems to have a reason for being. Another time that same year we wrote Mother’s Day poems to submit to the local paper. I could not write about Mother’s Day specifically because firstly my parents were Jehovah’s Witnesses but also because I didn’t have lovely, appreciative things to say about my mother. So in my mind I was writing about what my mother was not, and it won third place in the paper. The winners got a gift certificate for an ice cream date with mom. When I told my mom, she thought the poem was adorable, and true, not the criticism I had intended it to be. So poetry was a gift, a destined thing, and a secret. It didn’t matter if people took different messages away from it. They have their thoughts and interests, and the writer still has her voice and intention.

For Solace in particular, I did at different times ask early readers if they thought I perhaps wasn’t really a poet because my form was so long, and even still a level of detail and full perspective or the ability to create context through back story is left out. I battled with the advantages and disadvantages of poetry versus prose, but the story chose poetry as it form perhaps precisely because of the advantages of some of those disadvantages.

I think it’s Stephen Dobyns who wrote that word formations in poetry reflect contemporary reality and that, because of the fast-paced fractured media-influenced lives we now lead, writing in fractured forms has become a more accurate medium for art. When I read that, it made a lot of sense to my experience. It made me think of my first experience of coming across Ferlinghetti’s Coney Island of the Mind. The title is such a perfect reflection of the mind, but inside the book his use of the page as canvas not only matched content but also added an extra level of thought about the fractures, why were they there, each in their particular, chosen spots? I had my own theories and answers, and although I’ve read a lot of literary theory and criticism over the years, I like that my interpretations are forever valid in my reader experience. Even if Ferlinghetti walked up to me and said, “I broke that line that way because…” it would only matter in my interpretation if I felt it matched the actual content and effect of form for me, regardless of what he intended in writing it. That’s art, and I find it intriguing… just like that first interaction between my mother and my poetry.

So Solace is about broken lives and broken selves. Poetry is its natural form, and the gaps and doubts that poetry leaves are part of that form that bring writer and reader into discussion on a sort of metaphysical plane inside their hearts and minds, meaning that the writer considers the reader’s possible interpretations and reactions and tries to direct or in some case not direct certain interpretations but, in the end, it is the reader sitting with the text wondering about the writer. They’re on the same plane at different times and so although they influence each other’s thinking, they do not fully interact or intervene, which is not unlike what has happened in the lives of we seven children protagonists in the book.

Q: You talk about the nature of memory in Solace, and it’s one of the things that I explore in my own fiction. During its writing, did you find yourself challenging your own memory as you stripped back the layers?

Probably the biggest conflict with memory, even in a detailed memoir such as Solace, is deciding how much to tell and not tell. The narrative voice explores the effects of this, saying the readers or listeners “think they know how it was” in a sort of accusatory tone. And they do know. After reading, readers will know some details that not even my closest friends know, details that none of my siblings chose to be published, but these are only a few representative moments of a lifetime of seven individual people’s moments. There is no way to represent the complexity of emotion or experience, but that is a good and necessary thing. We need to keep something of our histories and identities for ourselves. When you tell a memory it’s a leap of faith, a giving in to the intimacy of trust. It’s a difficult thing to try to represent your truth and the truth of others, but trauma bonding (unfortunately) keeps those stories alive more than the tellers probably want to. We move on with our lives, finally allow ourselves to create an identity and a world we have chosen, but each time something connected to the family history happens, we are pulled back into the current crisis and to the retelling of the connected memories.

Solace has a few parts that were actually much shorter, undeveloped early writings from my earliest college years, some fifteen years ago. I didn’t have the skill to write them as they needed to be written and, though I was in college, the violence certainly hadn’t ended. When Solace started to really become a standalone book, I had recently taken my youngest sister and brother (ages thirteen and five) into my home and had started a custody proceeding against my father and mother. Some of the book was written while waiting on court benches after hearing my siblings testify in front of a jury. The custody case was combined with my parents’ divorce proceeding in Supreme Court, and my father had insisted on his right to a jury trial. So I wasn’t left to my own devices to select the “representative events” because here were my siblings testifying for themselves. It was very hard to watch; although we’ve all spoken many times about our upbringing, this pained us. It was heart-wrenching before, during, and after the trial to watch my grown siblings cry and tackle the “why” of it all. I could see both the little kids of many years past and the new grown people they had become combined in their eyes. It’s still a very vivid image for me as I’m sure it is for them. So the challenge was not in uncovering the memories themselves, but in trying to create a book that I felt was true to my siblings’ complexities as well. Thus, in writing Solace I was also in a similar position to the reader who will never know. I was there. I lived it alongside them, but seeing the different effects on each of us, I know that as much as I think I know and as much as I’ve tried to bring voice to it all, it’s never the whole truth.

Q: You zone in on very specific imagery, which you bring the reader back to time and time again – the scent of orange peel, the ash, the snow, a red hat. I thought this gives the piece a very hypnotic quality. Was this your intention?

Memory is backward and forward moving. Solace is mostly chronological, but some of the physical items or specific physical memories become markers to move forward and backward and create layering that aides the commentary. It’s good to hear that they have a hypnotic quality because one of the things I wondered about in my process is how much the reader would link up the pieces and if these layers were apparent to more than the standard academic reader who might be studying or seeking such things. Some qualities of a layered, abstract, fragmented form might be more familiar in the poetry crowd, but the dedication is “for the many.” When making these structural decisions I thought, “well when I was a teen I was picking up Hejinian and Ferlinghetti and Cummings.” Perhaps I didn’t understand the crafting as I do now, but these texts grabbed me and made me think. It is my hope that Solace remains accessible on different levels to different readers as those texts were for me.

Q: Obviously, Solace was a standalone piece. Can we expect to see more writing and if so what form will it take?

I’ve dedicated a lot of time to Solace, but in between the many rounds of revising and editing I’ve started other projects. Now that Solace has found a place in the world, I think I’ll be able to focus on completion of some new work. That’s exciting for me. I have another long form poetry manuscript titled Twelve Stations in Transit based on portraits of people I encountered during my first teaching job in Brownsville, Brooklyn, a very disadvantaged, crime-filled, and somewhat forgotten corner of New York City. The realities those kids live everyday created a similar drive to give voice, so that will probably be the next priority. I have two partial novels (Rain, the other is as of yet untitled) which I hope to someday complete, and a budding collection of short poems, which is quite a feat for me since it challenges me to work in brevity without the level of detail I am accustomed to using to create layering. It’s good to have other projects to switch off to. There were times I didn’t look at Solace for six months or more, and the separation gave me a greater ability to criticise my work when I returned to it.

To look inside or buy: Solace: A Memoir in Verse

Q: Colleen, thank you so much for speaking to me today and for sharing your story. Where can we find out more about you and your work?

I have a blog on teaching and writing that I intermittently write. There are some excerpts from other works in progress on there. I’d love blog post suggestions! My book is now on Amazon, and of course my publisher Vine Leaves Press can also be found on Facebook.

Remember, if you enjoyed this post please share it. If there’s anything else you’d like to ask Jane, leave a comment.

To have future posts delivered directly to your in-box, visit the side bar on the right and subscribe to my blog, or to find out about new releases, competitions and freebies, subscribe to my newsletter.

And if you’re an author and would like to appear on Virtual Book Club, please fill in a contact form.

One comment

This was a sensitive and thoughtful interview with questions that brought us to the heart of the writing.