This week’s Art in Fiction focuses on novels that are set in the mecca of modern art, Tate Modern.

One of my favourite reads in recent months was Harriet P Paige’s Man With A Seagull on his Head, which was nominated for Not The Booker 2017.

Paige perfectly pitches a portrait of outsider artist Ray Eccles (real art movement, imaginary artist), who, rather than being absorbed into the mainstream, will always remain an outsider; who creates images of one unknown woman out of obsessive compulsion rather than for the joy of it, or to practice his technique, and who has no interest in his work once it exists.

The novel is peopled by a wonderful cast. The unfulfilled promise of a young woman who feels powerful and special, but who goes on to be overwhelmed by motherhood. The loneliness of the unfulfilled married woman who discovers that she was the artist’s muse. The journalist who believes that bringing artist and muse together will give her the big break she’s been waiting for. The artist’s patrons who feel that, having discovered Ray and brought them into their home, he owes them more than he’s capable of giving. The wife whose money cannot buy her the things she craves (I suspect she doesn’t really know what they are). The husband with an eye for talent but who is driven to despair by the lack of his own. And the damaged daughter who concocts an extravagant plan after inheriting her mother’s wealth.

But the author’s real talent is for describing how art can make us feel, both when we connect with it deeply, when it overwhelms us or when the meaning eludes us. And this is reflected in the sense of loneliness that permeates the novel as a whole, showing how, despite best efforts and intentions, we often fail to make deep connections with one another.

The novel ends with the artist’s house being towed up the Thames and being installed as an exhibition in the Turbine Hall at Tate Modern, the kind of exhibition that is far easier to stage in fiction than in real life (a joy that I discovered for myself when writing the climax of Smash all the Windows).

Art as a talking point

Carol Cooper is a doctor, journalist, and novelist. After a string of health and parenting books and an award-winning medical textbook, she turned to fiction with her debut One Night at the Jacaranda.

Her latest novel Hampstead Fever was picked for a front-of-store promotion in WH Smith travel bookshops. Carol is President of the Guild of Health Writers and often appears on TV and radio. She lives in London and Cambridge and has three adult sons. You can find out more on her blog Pills & Pillow-Talk or follow her on Twitter @DrCarolCooper

Here, she explains why she brought two of her characters in One Night at the Jacaranda to visit the Tate Modern.

While imagery plays a large part in my writing, images rarely feature. The reason, perhaps, is that I’m too much in awe of artistic talent. My mother was a prolific artist as well as a writer, and, armed with a vivid visual imagination, she could draw anything at all. A commission for a watercolour of female rabbit doctors duelling in a forest? No problem.

Alas, I inherited none of that skill, though I can produce a passable sketch of a car if I’m in a carpark long enough and the car doesn’t move.

In One Night at the Jacaranda, Karen and Geoff are on their second date. They are just two of a motley group of Londoners in the book, each of them looking for someone special and ending up finding themselves.

Karen is a newly single mother of four, while Geoff is a stressed family doctor who has a five-year old son. Although they are at the Tate Modern for the Rothkos, it’s in the Turbine Hall where they most engage in small talk. I enjoy Rothko’s work very much, but I might have run out of dialogue after ‘Love those colours’ and ‘I never realized the canvasses were so huge.’

My thinking is, shall we say, quite concrete. Somehow Karen and Geoff find more significance in the crack in the floor than in the exhibit.

Here’s the scene.

‘A deceptively easy read which punches well above its weight, leaving you reflective and thoughtful and wishing there was a sequel.’

‘Alternately entertaining, witty, outrageously funny, poignant and dark, I would highly recommend One Night at the Jacaranda to lovers of intelligent women’s fiction.’

They stared at the crack in the floor in the Turbine Hall. It symbolized something, but what?

“The question is,” said Karen, “who put it there?”

“Here’s another question: how long has it been there? Are there any other cracks like this one? Could it be part of some arcane religion?”

“And is it getting bigger? How many coins, biros, and hairpins do you think fell down it before they filled it?” She examined it like a child. Others, mostly men, were doing just the same. She asked Geoff if he thought that meant men were more infantile. Or were they more likely to investigate things, which might be why most scientists were male?

“Maybe it’s in the genes,” said Geoff.

This rang a distant bell. “You think all of that’s down to one little Y chromosome?” she asked.

“Not necessarily. It could be X-linked, like haemophilia. Which is why a few women have it, but mostly men are affected.”

Karen had another theory. “How about if everyone has the investigating gene? But, in the case of half the population, they end up having to keep house, cook dinner, and look after the kids. So they don’t get a chance to express it.”

“Are you by any chance suggesting that men are indulged and kept in a state of prolonged infantilism where they are exempt from chores?” said Geoff in mock horror.

“You might very well think so.” Karen smiled. “I couldn’t possibly comment.”

Two young children came careering at them, making noises like gunfire. Geoff watched them, and she couldn’t work out if he was happy or sad. Then he got another one of his infernal texts.

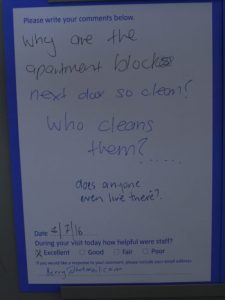

Talking points: ask for comments at your peril

By way of illustration of how we impose our own meaning on art, this excerpt from Smash all the Windows shows how the same piece can take on a very different meaning.

A former power station, the Tate Modern makes no effort to disguise its industrial credentials. Odd that people campaigned to save the structure. Unlike St Paul’s, it’s not an easy building to love. But, then, it houses art that isn’t always easy to love.

They locate Eric at the entrance to the Turbine Hall. Maggie looks at him anew, unsure of herself. Words that should be simple stutter inside her. I never got the chance to thank you.

“Ah!” he greets them. “The wretched and the brave.”

Maggie assumes it’s Shakespeare. After all, they’re only a stone’s throw from the Globe. “Which am I?”

“The brave, of course.” In the nervous energy Eric exudes is a clear sense of sacrifice. It seems so obvious now, she can’t understand how it has remained cloaked for so long.

Jules clasps him by the hand. “You see, we have a new accomplice. Maggie is going to write our wall labels.”

This is news to Maggie, who has never thought herself much of a copywriter. She smiles and taps her notebook as if she knows exactly what’s expected of her.

“Great.” Eric holds the door open for her.

I never got the chance to… It cannot be this hard.

A carpeted floor slopes away in front of them. An adult couple roll over and over each other as if they’re children playing and it’s a grassy incline. People picnic, sitting cross-legged. A toddler walks in circles chewing on the ear of a toy rabbit, while another shrieks repeatedly, creating echoes in the vast space.

“Isn’t that Led Zeppelin he’s singing?” says Eric.

“Right!” Jules gets the joke before Maggie does. “A Whole Lotta Love.”

Once again she’s the new kid who hasn’t made any friends. They walk and Maggie finds her voice. “I haven’t been here since they finished the extension. It changes the way you feel about the space, doesn’t it?”

“Definitely,” says Eric, and points to the meandering crack on the floor, what was originally an art work. “I really like how they’ve made no attempt to hide the repair.”

Maggie lets her eyes follow the full length of the concrete scar.

Jules stands alongside her. “The Visible Fracture,” he says. “You know, in Japan, they repair broken pottery with gold. The repair becomes part of the history of the objet. It is like us, n’est-ce pas?”

So complete is Maggie’s sense of being damaged, and of the damage being on display for all to see, that she stifles a gasp.

Eric is striding about. “So, they’re giving you the Turbine Hall.”

The damage is part of my history.

“Well, you know, an overnight success like me…” Jules puts his thumbs in the small of his back and looks up with a critical eye. “We will have to see if we think it will work.”

***

If you enjoyed this post, you may also be interested to read about how I used art as an expression of grief in my novel, Smash all the Windows.

If football isn’t your thing, now is the perfect time to discover new fiction.

To have future posts delivered directly to your in-box, visit the sidebar on the right and subscribe to my blog, or to find out about new releases, competitions and freebies, subscribe to my newsletter and I will send you a free copy of my novel, I Stopped Time, as a thank you.

While I have your attention, can I please draw your attention to my updated Privacy Policy. (You may have noticed, they’re all the rage at the moment.) I hope this will reassure you that I take your privacy seriously.

Remember, if you enjoyed this post please share it.

If you have subscribed to my blog but no longer wish to receive these posts, simply reply with the subject-line ‘UNSUBSCRIBE’ and I will delete you from my list.