Virtual Book Club: Jane Davis introduces An Unchoreographed Life

Now available on Kindle Unlimited (free to subscribers)

That’s right folks. I’ve hi-jacked my own author interview series to cast the spotlight on my 2014 novel, An Unchoreographed Life, one of two of my novels that are now available as part of Kindle Unlimited.

You already know who I am, so let’s get straight down to the nitty gritty.

Let’s start with the title. How did that come about?

An Unchoreographed Life is the phrase with which Margot Fonteyne described her tumultuous off-stage existence. It seemed an ideal choice for my story of a ballerina who turns to prostitution when she becomes a single mother. (Although the book’s working title was Pelican Park – see photo!)

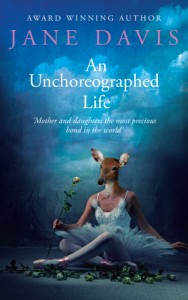

Your book covers receive a lot of praise. What was the concept behind this one?

I was absolutely clear that I wanted to avoid an image that hinted at erotica. Told partly from the perspective of a six-year-old, my novel has more in common with Henry James’s What Maisie Knew rather than Belle de Jour. I described a scene from the book, where my main character Alison comes face to face with a deer. I asked my cover designer Andrew Candy if it would be possible to combine the image of a ballerina with a deer. The image we arrived at suits the book perfectly: a woman who wears a mask and hasn’t been able to let go of her past.

In this 60 second video, Joni Rodgers explains why An Unchoreographed Life is perfect for your book club. And don’t forget – there are downloadable questions for book clubs on each book page.

“Don’t let this brilliant book pass you by!” Amazon reviewer.

“An extraordinary level of emotion brought on by some superb storytelling.” The Cult Den.

“A damn good read, and dare I say, important.” Linda Cooper.

Click here to look inside or buy. (Free for Kindle Unlimited subscribers.)

Where does this book sit in relation to your other novels?

The characters and the mother/daughter relationship in particular and key, but chiefly it’s a novel about identity. Alison has to ask herself the question, “If I can’t dance any more, then who am I?” Ballet has been such a huge part of her life, she has sacrificed so much for it, but after she becomes a single mother a return to the stage becomes impossible.

Where did you take your inspiration from?

As usual, it was a mix of ideas that gradually came together.

I grew up within the footprint of Nelson’s paradise estate. The story of his mistress, Emma Hamilton, always fascinated me. Poverty forced her to resort to prostitution, but she later became a muse for artists such as George Romney and Joshua Reynolds. Cast aside by an aristocratic lover, she went on to marry his uncle. And then, of course, she met Nelson. Completely self-educated, Emma continually reinvented herself, mixing in diplomatic circles and becoming confidante of both Marie Antoinette and the Queen of Naples. But despite all this, forgotten by her rich friends, she died in poverty. So I wanted to introduce a mix of fortunes; not just one huge rise followed by a huge fall, but several.

I already had a clear understanding that had I been born in another age, the chances were that I would have been either a domestic servant or a prostitute – quite possibly, both. Prior to 1823, domestics under the age of sixteen worked a sixteen-hour day in return for ‘bed and board’, an extremely generous description of what was on offer! When they reached the age of sixteen, they were cast out to fend for themselves.

As the recession deepened, the number of sex workers in London rose to the highest level since 1700. Added to the mix, I was gripped by a twist in a 2008 court case, when it was ruled that a prostitute had been living off the immoral earnings of one of her clients. The case also challenged perceptions of who was likely to be a prostitute. The answer turned out to be that she might well be the middle-aged woman with the husband and two teenage children who lives next door.

The links between ballet and prostitution are well documented, aren’t they?

Absolutely. The Dictionary of Victorian London named ballet-girls among those professions where workers routinely supplemented wages with sex work (a list which also included dress-makers, straw bonnet-makers, silkwinders and shoe-binders). The author commented that ‘ballet-girls’ had a particularly bad reputation, which he described as ‘in most cases, well deserved.’ The primary cause? Poor remuneration, from which they were expected to by their own shoes and petticoats, silk stockings. But the author ‘Natural levity and the example around them; love of dress and display, coupled with the desire for a sweetheart; low and cheap literature of an immoral tendency and absence of parental care and the inculcation of proper precepts. In short, bad bringing up.’

In recent years, former solo ballerina Anastasia Volochkova accused the Bolshoi Ballet’s management of turning the theatre into a ‘giant brothel’. “The girls were forced to go along to grand dinners and given advance warning that afterwards they would be expected to go to bed [with guests] and have sex. When the girls asked: ‘What happens if we refuse?’ they were told that they would not go on tour or even perform at the Bolshoi Theatre,” she told Russian News Service.

This may sound shocking to refined twenty-first century ears but, as recently as 1905, the Encyclopedia Britannica still defined ballet as ‘lewd, obscene dancing.’

You’ve admitted in the past that you’re squeamish about writing sex scenes. Did you have to confront that head on?

Yes and no. I wasn’t writing a book about a sex worker. I was writing a book about a complex character thrown into circumstances she never expected to find herself in. The only way that Alison could cope was by telling herself that they were temporary. But I did feel a responsibility to show the lengths she had to go to in order to pay the rent and put food on the table. And so there is one scene.

I had already given Alison a coping mechanism. Whenever she has to confront something unpleasant in her new life, she slips back into the old. I used the ballet The Invitation. Alison effectively becomes the ballerina playing the young girl who is flattered by an older man’s attention, not realising what it is he wants. I watched the ballet and described on the page what I saw.

There was violence in the moment she realised that he didn’t only want to dance with her. The musical accompaniment was jagged and strange. You’d be forgiven for thinking it improvised, almost unmusical. There was a struggle. A series of lifts with his hand thrust between her legs, and, even then, she wasn’t sure what it was he wanted. Then, as he threw her about, spread-eagled, hooped her around his body, it became brutally clear. Clenching her jaw, Alison hated Cat for being right. Horrific to watch, those who didn’t turn away from the stage felt as if they’d borne witness. Finally, when it was over, she slid down his body to the floor.

Since the ballet is difficult to watch, I didn’t feel this was a cop-out. And the chapter isn’t about the violent client. It’s about Alison having to deal with the quick transition from quivering wreck to mother, because there is very little time before she has to pick Belle up from school.

Tell us a little about your research.

The settings were all places I knew. In fact, I’ve put together a short film with some of them here.

In terms of ballet, from the age of five, I took six years of lessons in a cold church hall to the accompaniment of an out-of-tune piano! Add to this Meredith Daneman’s insightful biography of Margot Fonteyn. But one thing Margot Fonteyn didn’t do was retire. And so for the psychological impact of how enforced retirement affects someone who was born to dance, I referred to personal accounts posted on the Internet, all of which described an identity crisis.

Inevitably, while the project was taking shape, I read Belle de Jour. Although it was never my intention to write a book about sex work, I needed to understand the everyday practicalities: how the author rotated use of chemists so that she didn’t come under suspicion; her eating habits; her trips to the beauticians; which of her friends did and didn’t know what she did for a living.

I also used the Internet extensively to source personal accounts, diaries, blogs and newspaper reports. How did sex-workers come to the attention of the police and social services? What were the reasons they ended up in court? (The answer was generally tax evasion and financial crime, things I already knew about from my day job.) How did sex workers see themselves? How did they view their clients? I also consulted The English Collective of Prostitutes, who kindly allowed me to quote them in a fictional newspaper article.

And then I began to imagine what life was like for the child of a prostitute. There was nowhere I could research that hidden subject. And it is always the thing that eludes you that becomes the story.

How difficult was it to get inside the head of a six-year old?

I remember childhood as being a very frightening place, with many secret fears and worries. Then there are the injustices you see so very clearly. All you can do is trust that the people in charge know what they are doing. So often, they don’t.

Aside from getting this across, my main concern was where to pitch the language for my six-year-old character when writing adult fiction. The books I turned to were What Maisie Knew, Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close, The Ocean at the End of the Road and The Night Rainbow. I researched developmental stages for six to eight year olds, but was then very much reliant on my beta readers to comment on whether they felt that the mother and daughter relationship had an authentic feel. Some felt that my child-character Belinda was too old for her age, some that she was too young. Some felt that my mother, Alison, was utterly irresponsible and deserved to have her child taken away from her, others that they would do everything that she did for their children and more. And so I concluded that I had written something that would invite debate.

Is there one question your writing brings you back to again and again? Do you think you will ever find an answer that satisfies you?

It took me some time to work out that the common theme running through my novels is the influence that missing persons have in our lives. (This shouldn’t have come as any great surprise to me since the death of a friend was what made me start to write.) In my experience, that influence can actually be greater than that of those who are present. In Half-truths and White Lies it was parents who weren’t around to answer questions. In I Stopped Time, it was an estranged mother. I addressed the theme head-on in A Funeral for an Owl which considers teenage runaways. And in An Unchoreographed Life Belinda grows up without knowing her father. Fiction provides the unique opportunity to explore one or two points of view. It is never going to provide the whole answer, but it does force both writer and reader to walk in another person’s shoes. And, in many ways, it is the exploration and not the answer that is important.

One comment

Sounds both intriguing and heartbreaking. Congratulations on another novel!