It’s not every day that one of your favourite authors agrees to an interview, so I was more than a little giddy when John Ironmonger said yes!

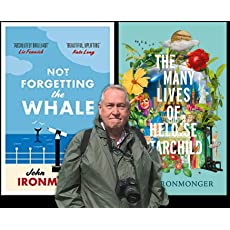

For those of you who have yet to discover John’s fiction, let me introduce you. John is the author of The Notable Brain of Maximilian Ponder, The Coincidence Authority, Not Forgetting the Whale, and, soon to be released The Many Lives of Heloise Starchild. His novels have been translated into seven languages.

John was born in Nairobi, Kenya. At the age of thirteen he was dispatched to boarding school in England (St Lawrence College in Ramsgate). He studied Zoology at Nottingham University, and went on to complete a PhD degree at Liverpool studying freshwater leeches and flatworms. This led to a period lecturing at a new University in Nigeria (the University of Ilorin).

John married Sue Newnes in 1975, and they have two children – Zoe, and Jon and three grandchildren.

In 1994, while Sue was serving on the Council of Chester Zoo, John wrote The Good Zoo Guide, a guide to all of the UK’s zoos and animal parks, which was published by Harper Collins.

The Notable Brain of Maximilian Ponder came third in the Guardian newspaper’s ‘Not the Booker Prize,’ and was shortlisted for the Costa First Novel Award.

The Coincidence Authority (published as Coincidence in the USA) was World Book Night’s ‘Book of the Month’ in September 2013, ‘The Bookseller’s’ Book of the Month for Oct 2014, and Waterstone’s Book of the Week in Sept 2014. Released as Le Genie des Coincidences in France, it earned a full page review in Le Monde, won the prestigious Prix de Lecteurs at Litteratures Europeenes 2015 and the Prix Bouchon de cultures.

It is John’s third novel, Not Forgetting the Whale, that will be the subject of our discussion today.

In 2015, back in the day when the word pandemic was not part of my daily vocabulary, I read two books on the trot that featured devastating and deadly flu epidemics. The first was Emily St John Mandel’s, Station Eleven. The second was John Ironmonger’s Not Forgetting the Whale.

Despite the potential in both books for the end of civilisation as we know it, both proved to be uplifting reads. Emily St John Mandel’s focus was how, even after so much loss, we are still surrounded by beauty. John Ironmonger’s zones in on a remote community in lockdown – something many of us can relate to now.

Q: When credited with predicting a pandemic, Emily (may I call her Emily?) responded, “There was always going to be another pandemic because pandemics are something that happens, the same way that earthquakes and hurricanes happen.” Experts have suggested that Covid-19 is the inevitable consequence of globalism. Is inevitable how you see it?

A: Like Emily (may I call her Emily too?) I can’t claim to have predicted the pandemic. I had an idea in my mind for a story set in a small community – very much like the village in Cornwall where I lived as a teenager – and I needed a dramatic back-story that would allow me to cut the village off from the rest of the world. The pandemic idea came from a very prescient article in New Scientist by Debora MacKenzie called, ‘Could a pandemic bring down civilisation?’ The moment I read this I understood the powerful potential for fiction. And of course, I agree both that pandemics are natural and inevitable, and that the breath-taking speed with which Covid-19 conquered the world came as a result of our unquenchable love for international travel. I don’t think those are opinions – they are a recognition of reality. But I’m nervous about pinning it all on the rather abstract idea of ‘globalism.’ Even without air travel Covid-19 would have found its way here eventually. European settlers brought smallpox, measles, mumps and typhus to the Americas and virtually wiped out native populations. I suspect that if Covid had shown up in China in the middle ages it would still have caused a global pandemic. But it wouldn’t have happened so quickly.

Q: Of course, you two weren’t the first authors to write about global pandemics. One example, Albert Camus’ classic The Plague was written over 70 years ago. An online conspiracy theory which is doing the rounds credits the American author, Dean Koontz, with predicting the corona virus outbreak in 1981. His novel The Eyes of Darkness made reference to a killer virus called “Wuhan-400” – the Chinese city where Covid-19 would emerge. To me, the interesting thing is not why you wrote about a pandemic, but why you wrote about it when you did. Was there something that made you think, the time is now?

A: Before I wrote Not Forgetting the Whale I wrote a novel called The Coincidence Authority about a man who is an expert at debunking coincidences (until he comes across a set of coincidences he cannot explain.) I mention this because the Dean Koontz story is so clearly an example of a striking coincidence. It isn’t remarkable to have chosen China as the source of the virus – and I’m sure Koontz did what all writers would do – he googled a list of Chinese cities, dismissed the famous ones (Beijing, Shanghai …) and those with names that he might misspell (Dongguan, Chonqing, Guangzhou …) and chose the one that he could type a hundred times without having to look back and check … Wuhan. No fiction writer has a crystal ball. We all invent stories. But we also do something that is harder to explain. We live for a year or more in the world we have created. During that time we figure things out because we lie in bed puzzling ways to make our stories work. We discover details that might not be immediately apparent to experts in a COBRA meeting, because we have lived through the situation. So when a writer like Koontz, or Camus is credited with prediction – it isn’t prediction at all. But it can still tell us things about the world the author has created, because they have lived there. They know it.

As for why I wrote the Whale when I did … it probably feels timely now, but I suspect it was just another coincidence. Oddly what Covid has probably done is to kill the pandemic story for a while. I cannot imagine writing one now.

Q: You mentioned crystal balls, but many authors have included levels of detail in their fiction that seem eerily accurate. In The Wreck of the Titan, published in 1898, New York native Morgan Robertson wrote of a vast ocean liner that was considered unsinkable. In his book, the Titan sets sail in the month of April only to collide with an iceberg in the Atlantic Ocean. The ship sinks with 2,987 passengers and crew. They died because there weren’t enough lifeboats on the ship. Fourteen years later… well, we all know what happened…

A: I do love the story of the Titan, but, as Thomas Post (the protagonist of The Coincidence Authority) would probably say, the story wasn’t all that remarkable even at the time. I’d refer you to a Wikipedia page called, ‘List of Ships Sunk by Icebergs’ where you’ll discover that at least 16 vessels had met their end in this way when Morgan Robertson was writing his novel – and he was writing at a time when small scale ships were giving way to great ocean liners. Many novelists want to create a big story so it was natural for him to imagine a huge ship, and why not call it Titan? I can also picture him pondering the dramatic possibilities offered by having too few lifeboats. The message for me from The Wreck of the Titan isn’t that Robertson saw the future, it is the tragedy that White Star Line didn’t read his novel and learn some lessons before they launched. Remember the novelist has been there. He or she knows what happens next.

Q: Interestingly, Emily St John Mandel’s new release, The Glass Hotel, concerns the financial collapse of 2008, whereas you combined the financial crash with a pandemic in Not Forgetting the Whale. Can you tell us how that came about?

A: When I wrote the Whale in 2015 it wasn’t too long after the financial crash. I originally saw the central character, Joe, as a kind of ‘Nick Leeson’ trader (remember him?) who has fled the city to hide from a set of disastrous trades. As the story developed it made more sense to make him something of a seer who predicts the crash. I also had the story of Jonah and the Whale in my mind – and you may remember that Jonah is a kind of prophet of doom.

Q: In 2017, the New Yorker crowned Margaret Atwood “the prophet of dystopia.” She famously replied “I am not a prophet. Science Fiction is about now.” Written in 1984 in West Berlin, The Handmaid’s Tale dealt with the question, if there was a totalitarian regime in the United States, what kind of regime would it be? How embedded in fact was your work of fiction?

A: So far as the Whale is concerned, I tried to make it broadly factual. By this I mean there was no need to invent any new technology. It doesn’t have a faster-than-light drive, it doesn’t require an unknown virus (the virus in the novel is identical to Spanish Flu) – and even the clever computer system, Cassie, is based on pretty mainstream AI. I have written dystopic fiction in the past where these rules don’t apply – but for the Whale I wanted it all to be able to happen today. Which it could. And is. Sort of.

Q: I’ve just finished reading The Mirror and The Light, Mantel’s final instalment in the Wolf Hall Trilogy. She was writing about a time when the plague was rife, and even those displaying what we would consider to be minor symptoms were dead two pages later. We’re so used to medicine providing and answer for everything and yet there’s no medicine for a virus.

A: I’m about 100 pages into The Mirror and the Light. Hilary Mantel, as ever, tells it how it is. And before we get too excited about every promising vaccine on the news, it might help to remember that no one has yet developed a vaccine for the common cold virus. The world spends about $8 billion every year on remedies for coughs and colds. That’s eight billion dollars for cures that don’t even work. Nothing cures the common cold. Nothing. How much could a pharma company earn if they had a cure that really did work? But they don’t, because viruses are tricky. And remember we still don’t have a vaccine for HIV even after a global effort and decades of promises. And flu vaccines are still a bit hit-and-miss. We might get a Covid vaccine. But we might not. In which case we, like the Tudors, might be living with this plague for a while.

Q: I was a teenager when it was predicted that HIV/AIDS would overshadow all illnesses that had gone before. (‘The tip of the iceberg’) Similarly when SARS and Ebola emerged, what seemed to be explosive threats fizzled out. Experts have said that something on the scale of Covid-19 is the natural consequence of globalisation. We’re also told that global warming is changing the spread of vector-borne diseases and the impact this has on populations not previously brought into contact with these viruses. In Biblical times, plagues were seen as manifestations of the wrath of and angry God. Today, there is much talk of the planet taking its revenge. Do you have a take on this?

A: The planet isn’t taking revenge. We are simply reaping what we have sown. Right now we are all, understandably, fixated on the Corona Virus. But if I was a prophet of doom (and I’m not, really) I would be shouting about climate change. Viruses come and go and it is all very unpleasant to those of us who live through them (or die), but climate change is the ultimate wrecker of worlds and it is the one thing we are doing now that will utterly screw up lives for hundreds of generations to come. Perhaps forever. (Feel free to replace the word screw with a stronger one.) Remember we have had five mass extinctions on this planet. One was caused by an asteroid. Four were caused by climate change. Remember too that we are on track for 5oC of global warming – and the last time the world was 5o warmer there was no ice at either pole and sea levels were 40 metres higher than today. Humanity faces being forced towards the poles where soils are too poor for our crops to grow. This is a cataclysm almost beyond imagination. But novelists had better start imagining it and writing about it. We need the stories just as we needed pandemic stories to help us to understand it.

Q: You wrote about your viral infection as an event looked at from the future, by which time myths had grown around the story, and had become part of St Piran’s oral narrative, which of course is a very powerful part of storytelling. Why was it important to you do this?

A: There is something mythic even about this pandemic don’t you think? I suspect we will be telling our grandchildren about it and exaggerating the discomforts and forgetting the details and eventually this too will become part of our global story. I liked this perspective. It worked for the story I wanted to tell.

Q: Not Forgetting the Whale focuses on a small community, asking when the chips are down, are we collaborative or competitive beings? Are you optimistic about what we’ll face on the other side of the madness? Do you think there will be any longer-term positives?

A: Someone once asked me this question at a book club, and I answered by saying I had faith in humanity, and I didn’t think we would end up hunkered down in caves shooting at each other. Then I added, ‘but I’m not sure about the Americans,’ and this earned a big laugh. But it wasn’t entirely a joke. I do worry that the cultural backgrounds and expectations of people might affect the way they behave. Here in Britain we hearken back to the blitz and this is part of our shared story; and we all love the NHS and cheer on the plucky nurses, and all this colours the way we act in a crisis. But in the USA they tell stories where the heroes are gunslingers and survivalists, and their health services are rapacious predators, and guns are trusted more than people, and it worries me that my rosy view of community might be a particularly British one. Nonetheless I do see positives from this madness. I think we will take a much more serious look at existential risks and be better prepared for the next one – be it another pandemic, or a tsunami, or an asteroid, or whatever. I hope we will appreciate more (and fund better) services like the NHS and care homes that we need so badly. And I hope we will all take a good long look at everything we are doing to this planet and rein back. If all of this happens it will be something.

Want to learn more about John and his writing?

Jump over to John’s Amazon Author Page, find him on Goodreads or follow him on Twitter @jwironmonger

You can also keep in touch with John on his occasional blog: http://notablebrain.blogspot.com/

To have future posts delivered directly to your in-box, visit the sidebar on the right and subscribe to my blog, or to find out about new releases, competitions and freebies, subscribe to my newsletter and I will send you a free copy of my novel, I Stopped Time, as a thank you.

While I have your attention, can I please draw your attention to my updated Privacy Policy. (You may have noticed, they’re all the rage.) I hope this will reassure you that I take your privacy seriously.

Remember, if you enjoyed this post please share it.

If you have subscribed to my blog but no longer wish to receive these posts, simply reply with the subject-line ‘UNSUBSCRIBE’ and I will delete you from my list.

One comment

Thank you Jane.

I must say up front that I know John and worked with him and ‘around and about’ him for many years.

I have bought and read all his books.

His writing style makes complex topics so accessible and understandable with that special talent to take you off to meet real people in real places through the pages in a book.

I just wanted to tell everybody that, as I am so proud to know him and his work, and thank you for reminding me of his great talent.

Sean Brennan